© Simon Knell, all rights reserved. From Simon Knell, Immortal remains: fossil collections from the heroic age of geology (1820-1850), Ph.D. thesis, University of Keele, UK, 1997.

The discovery of Kirkdale Cave in July 1821, which ignited a local fascination for geology also left a legacy of interest in the fauna of what today would be called the Pleistocene.[1] The story of the cave is well known and need not be reviewed in detail here.[2] Initial mapping and excavation was directed by William Salmond, George Young and William Eastmead, of York, Whitby and Kirkbymoorside respectively. It was uncovered during quarrying operations on the eastern bank of Hodgebeck near Kirkbymoorside, and lay within easy reach of residents of York, Whitby and Scarborough. At Vernon’s request William Buckland visited the cave in December. In a paper, read before the Royal Society on 21 February 1822, he transformed this inert pile of bones into a dynamic ecosystem inhabited by a local population of hyenas.[3] Within nine months this work had earned him the Copley Medal from the Royal Society and Buckland’s hyenas had become a national sensation.

In presenting the medal, Humphry Davy said it had been suspected for some time that such finds in Britain and elsewhere represented faunas which had once lived in those countries. ‘Yet that this had never been distinctly established till Professor Buckland described the cave in Yorkshire, in which several generations of hyaenas must have lived and died’.[4] As a result two theoretical views might be taken of the subject: ‘one, that the animals were of a peculiar species fitted to inhabit temperate or cold climates; and the other, which he thought the most probable, that the temperature of the globe had changed’.[5] Perhaps further proofs might be found amongst the diluvial remains of the county.

Through this publication Buckland established his position as the country’s pre-eminent expert in organic remains, particularly amongst the landed gentry and provincial philosophers aspiring to scientific notice. He utilised this popularity to extend his existing network of observers such that he would receive the very latest intelligence on fossils in provincial England and elsewhere. He further consolidated this position in the following year with a more extensive treatment of diluvial deposits.[6]

Interest in cave faunas in Britain dates back to around 1816 when excavations for limestone for Plymouth breakwater revealed a cavern containing the bones of hyena, rhinoceros and other animals. These were amongst the first fossils Vernon sought to acquire for the Yorkshire Museum through his contacts with Lady Morley.[7] At this time Buckland visited the great German bone caves which were then producing prodigious amounts of material.[8]

Through the amalgamation of Yorkshire’s three largest collections of Kirkdale fossils the Yorkshire Philosophical Society was born. It was the best possible start for a body with such high objectives in geology; as a repository, at least, it was thrust into the realm of headline science.[9] It could also boast a direct link to the man at the centre of this research. These specimens were to become touchstones for future development; relics of almost religious significance which encapsulated the new philosophy of selfless science and benefaction.[10] Fossil remains associated with the diluvium continued to form an underlying interest within the Society. Towards the end of the decade this was to culminate in the Society’s most assertive and systematic attempt at research motivated collecting and perhaps the first systematic palaeontological excavation in Britain.[11]

The Yorkshire Philosophical Society added further Kirkdale material from other members, and mopped up the remnants of Atkinson’s and Salmond’s collections on their death. Some of this material was passed to the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society and elsewhere. There were also fossils from Kirkdale in the museums in Hull and Whitby. Here too they were amongst the most valued items.[12]

The Kirkdale finds continued to generate considerable discussion amongst local philosophers long after Buckland’s paper was published. The three original explorers William Salmond,[13] George Young[14] and William Eastmead[15] criticised Buckland’s conclusions in private, in lectures, in exhibitions and in publication. Young’s interest in Kirkdale had been rekindled in 1827 by an article which appeared in Philosophical Magazine. The headline read: ‘Discovery of fossil hyaenas in Kent’, which was translated for local consumption, possibly by Young, into ‘A new Kirkdale Cave’.[16] In June 1827, John Braddick,[17] a land and quarry owner living just south of Maidstone, discovered an assemblage of bones in 15 foot deep fissures in his quarries. He informed the Geological Society immediately; geography played a large part in the interest generated.

From its proximity to the metropolis, it affords to the London geologists a more ready opportunity of becoming personally acquainted with the phenomena connected with such discoveries, than has been before possessed; no assemblage of bones having been previously met with nearer than Somersetshire.[18]

Buckland and Murchison were two of a party of six men who left on the Maidstone coach ‘and threw the Kentish men into alarm’,[19] though it was only the hero of Kirkdale who was named in reports. As Murchison recounted to Vernon: ‘Buckland got in about twice his length & burrowed with great energy – his opinion being that the fissure may still lead to a cave’. But, despite the discovery of a considerable number of hyena teeth and other remains, no cave was found. The collected fossils were deposited in the Geological Society’s museum. The discoveries at Kirkdale may have encouraged Braddick to take a closer look at this phenomenon in his own quarries – quarries which had been worked for centuries. Certainly, without a burgeoning interest in geology and Buckland’s extraordinary discourse on the hyenas of Yorkshire, the Kent discoveries may not have been made. On the coast of Yorkshire, the poorly educated artisan had little difficulty in exploiting an obvious resource and a ready market. However, Kent’s ‘Kirkdale’ demonstrated that society’s failure to educate or encourage inquisitiveness in the artisan meant that the significance of more complex deposits could not be recognised. The heavily hierarchical staffing structure of such quarries would separate the finder from the philosophising landowner, until such time as the curiosity of the latter was raised by news of discoveries elsewhere.

Mr Braddick’s workmen say they have frequently found them in his quarries, but always neglected to preserve them; one fine head was thus lost but a few weeks ago: enough, however, has already been done to show that the hyaena was among the antediluvian inhabitants of Kent, as it has been proved to have been among those of Yorkshire and Devon; and it is highly probable that if the proprietors of quarries in this country will reward their workmen for preserving whatever teeth, or bones, or fragments of bones, they may dig up in the course of working their stone, many similar discoveries will soon be made.[20]

Nearly all the major discoveries of similar antediluvial remains during this period arose from excavation associated with stone extraction or agriculture. The discovery of bones at Kirkdale, relied upon the chance find of a visitor to the region; not on the men involved in quarrying. The publicity given to these discoveries in Kent and Yorkshire would if nothing else, raise an awareness amongst landowners that such finds might arise almost anywhere.

The elephants of the Holderness coast and elsewhere

Throughout the 1820s the semi-fossilised remains of elephants and deer were frequently uncovered along the coast to the south of Bridlington. These, together with occasional finds from the low lying land to the west of the Yorkshire Wolds, continued to keep interest in the Kirkdale fauna alive.

It was Buckland who, having just completed his Reliquiae Diluvianae, first brought Vernon’s attention to the potential of the Yorkshire coast. He was well aware of the Bridlington collectors and dealers. A ‘museum’ in these coastal towns was more likely to be a dealing establishment than a philosopher’s hoard.

At Bridlington there is a man[21] who keeps a small museum and has in it some good things for wh[ich] he asks enormous prices, among them is one wh[ich] he w[oul]d not sell me at any price but might give to the Museum perhaps, viz., a portion of a tusk of Elephant found near there, so perfect that it is still hard ivory & several snuff boxes have been made from it. The Residuary Portion sh[oul]d be rescued coute qui coute[22] from such Desecration. It is the only tusk yet found in England in so perfect a state; that of Dr Alderson’s I mentioned in my last is nearly as perfect but not quite so.[23]

It was probably this find ‘of fine ivory’ which had been reported in Philosophical Magazine in 1822, though it is possible that the latter refers to John Alderson’s specimen. The article stated that a ‘portion of a tusk, about thirty-eight inches in length, twenty inches in circumference at the lower end, and weighing four stone two pounds’[24] had been found at Atwick just north of Hornsea. It seems the tusk was too valuable to be sold in its raw state. Nearly two years later, Buckland acquired a silver rimmed box made from this ivory, which he had inscribed and in which he placed some Siberian mammoth hair from the mouth of the River Lena. He perceived the two materials as equally remarkable survivals.[25] He made a gift of these to York. Phillips, at the time, remarked how such specimens provided further evidence of a local fauna of exotic animals: perfectly preserved teeth, tusks and horns buried beneath deposits in which the hardest of rocks are worn smooth and round by distant transport.[26] Proof indeed that these were not remnants of the deluge.

Throughout the 1820s elephant remains from the Holderness coast continued to pour into the York collections. The frequency with which they were donated, and the nature of the donors – men such as Sir George Cayley who were not noted field collectors – suggests that this, in part, reflects the availability of these fossils in Wilson’s, Cowton’s and other dealerships along the coast. Phillips always saw such material for sale when in Bridlington.

Another source of similar remains, was the peat deposit located at Owethorne much further to the south. James Backhouse and Chris Sykes contributed several specimens from this site, over a number of years. Phillips was in no doubt that the peat and the bones it contained were of Recent origin and, contrary to a paper by Richard Cowling Taylor,[27] lay above the diluvium.

In addition to the coast, the vales of York and Pickering also produced sporadic and fragmentary finds of subfossil bones – a Bos horn from Alne, a stag’s horn from Scampston, an elephant tooth from Overton and so on. A gravel pit at Hessle attracted particular attention from Vernon and Salmond; it again clearly demonstrated the fate of fossils prior to the age of the provincial philosopher.

At Hessle in the diluvial gravel lying in the Chalk, bones are found, dispersed, at a depth of twenty feet and below a very hard seam of conglomerated flints. They are chiefly those of the Horse. A man who works in the Gravel Pit informed me that he had once met with the bones of a much larger animal and teeth four times the size which had been thrown away and could not be recovered.[28]

Buckland encouraged Vernon to continue his researches into this deposit and as a result numerous horse bones entered the York collections.[29] Excavations for a canal at Ferrybridge encouraged similar interest when the Society’s local observer, the Rev. William Richardson, reported that the workmen had found a petrified tree and nuts. This was sufficient to encourage Phillips to visit the site.[30]

Members were also sending bones and teeth back from further afield – from Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Norfolk, Derbyshire and even France. Other parts of Britain were experiencing a similar upsurge in the discovery of these types of remain. The Cambridge Philosophical Society, for example, uncovered a large and diverse assemblage of fossil bones near ‘Bamwell’ in 1824.[31] This year also saw two important cave discoveries, from which material entered the York collections. The Rev. John McEnery presented a collection of teeth, bones, and casts from Kent’s Cavern in Devon ‘as a small accession to the fossil remains from Kirkdale’ together with a long communication on the nature of the discovery.[32] He had given a similar collection to Cuvier, who had expressed an opinion on them, which added further value to the specimens now in the Yorkshire Museum. The second collection of bones came from Banwell Caves in Somerset, a gift of the Bishop of Bath and Wells who ‘intends to provide a similar supply to all the principal public museums in this country’.[33] Such discoveries served to keep philosophical attentions focused on these antediluvial faunas.

The philosophical societies had reason to hope that a local Pleistocene deposit might provide a complete skeleton to rival Whitby’s reptiles. Such specimens were known, and none more so than the ‘Giant Irish Elk’[34] found on the Isle of Man at the beginning of the decade and presented to the museum of the University of Edinburgh.[35] Its draw was such that Phillips made a pilgrimage to see it on his tour of Scotland in 1826: ‘the noble elk from the Isle of Man, which bears its head on high. “The ‘Regius’ Museum is indebted to his Grace the Duke of Atholl for the magnificent specimen of the Irish Elk”’.[36] Hopes were raised higher when the skull and antlers of this species were discovered at Atwick near Skipsea on 31 January 1827 and came into the possession of Arthur Strickland; it measured 6 feet 8 inches between the tips of the antlers.[37]A complete specimen was not, however, found in Yorkshire and in the mid 1830s the Yorkshire Museum acquired a Waterford skeleton from G.L. Fox,[38] which was later completed through exchanges with the Earl of Enniskillen in 1840.[39] By this means the Yorkshire Museum became the first in England to display such a specimen.

Bielsbeck[40]

In 1829, a discovery was made in the south-eastern corner of the Vale of York, which resulted in the Yorkshire Philosophical Society’s most earnest attempt at research driven collecting, but also to a long standing feud with philosophers in Hull. The site has also continued to stimulate interest from successive generations of Pleistocene geologists to the present day. In some respects its exploitation mirrored the earlier excavations of Willson Peale in the United States, who sought, located and excavated a complete skeleton of the mastodon for his museum.[41] It was probably hoped that Bielsbeck might also produce a complete skeleton, but the York philosophers seemed happy enough simply with the science it would generate.

The first indications that the area to the south of Market Weighton might preserve important diluvial material came at the very end of 1825. It was then that the Rev. Henry. Mitton wrote to William Danby concerning the finding of an elephant tusk at Harswell. Danby was one of the Vice Presidents of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society and a keen collector. In 1824, he had found the partial remains of a ‘gigantic Bos’ in a peat bog on his estate, Swinton Park, 10 miles north of Ripon. Mitton, who appears to have been a resident of Harrogate, knew Danby and his interest in geology and enthusiasm for the new society in York. Indeed members were encouraged to extend the York network through their own contacts elsewhere in the county.

Mitton’s letter contained information concerning a ‘horn’, nine feet long, found at a depth of 7 to 8 feet, in a marl pit on the land of one of his tenants at Harswell.[42] Within a few weeks Danby had acquired what remained of the specimen, and donated it to the Society’s museum in his own name. Finds of such extraordinary dimensions suggest, as Phillips surmised from coastal evidence, limited pre-burial transport and therefore the remains of a local fauna. It was some time later that the Yorkshiremen realised the significance of this find and wrote to Danby for exact details of where it had been found.[43] As Mitton explained to Danby, the farmer had been digging a marl pit about 10 feet deep, in strata consisting of ‘blue, red and white layers’; the tusk had come from a trench just 2 feet wide. That this Harswell specimen was potentially an early indication of the same geological phenomenon which preserved the Bielsbeck fauna never became apparent to the York philosophers, or to any subsequent workers.

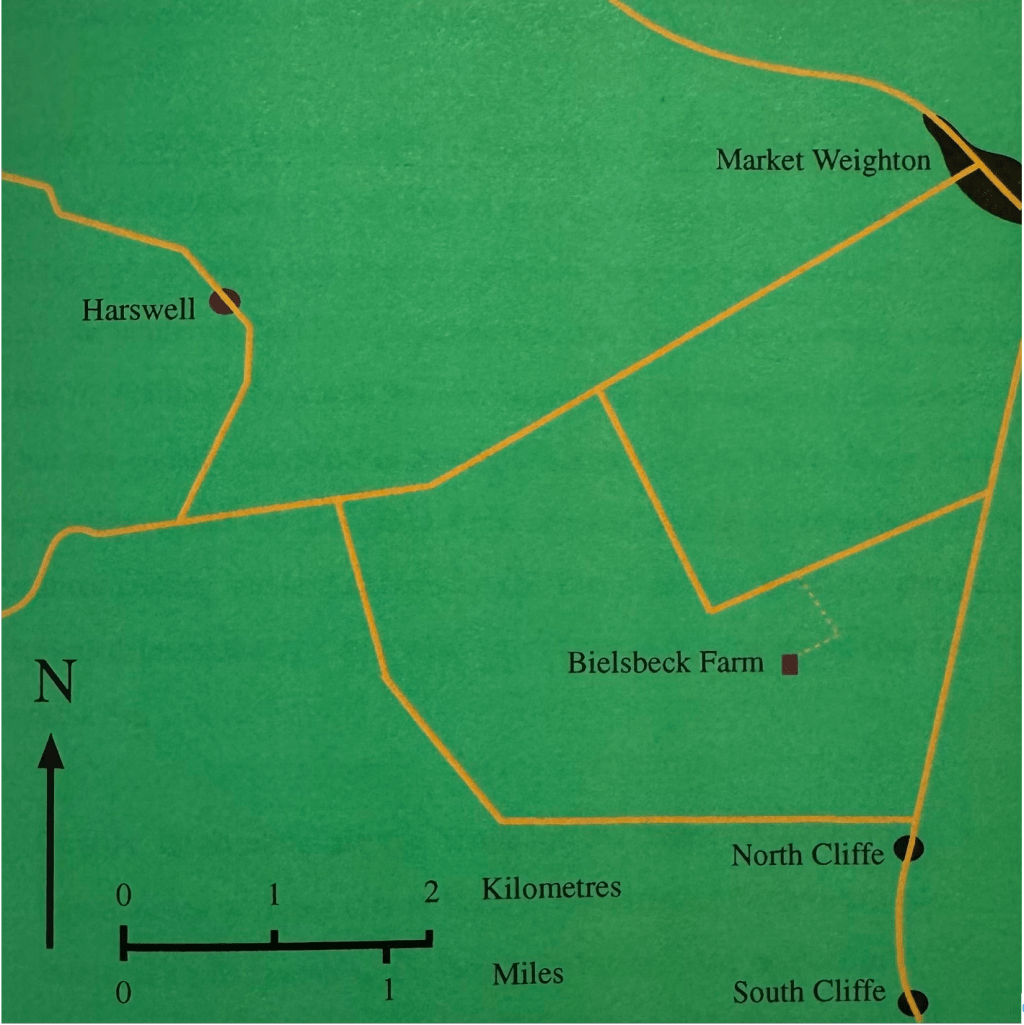

Figure 7.1 Map showing Bielsbeck Farm

In 1828, a tenant farmer of the name of Foster, living in the solitary farmhouse of Bielsbeck[44] one mile north west of North Cliffe, found a bone whilst excavating marl to improve poor sandy land near his house. This he kept but apparently thought little of it. The pit, which measured approximately 20 yards by 8 yards, flooded during the winter but was left open for further excavation in the following year. When these excavations began more bones were found, and continued to be found. These finds were brought to the attention of William Hey Dikes, honorary curator of the Hull Literary and Philosophical Society. Bielsbeck Farm is almost equidistant between York and Hull.

Dikes lost no time in visiting Foster’s house to see the bones and had little difficulty in identifying them as coming from bear, elephant, rhinoceros, deer, ox and horse. He wrote to Phillips immediately, and Phillips replied by return of post obviously excited by the letter. He implored Dikes to go public with the find or be ‘a traitor to the cause of science’.[45] Phillips, who was to leave for Europe the following week, intended to visit the site but was equally interested in getting Dikes on the right track. Even from this first letter Phillips could see that these finds deserved further investigation and possibly excavation; nothing similar had been seen in Yorkshire since Kirkdale. Buckland was to be informed immediately. But what should the Hull man be looking for? Phillips provided a list:

Identify if possible all the shells of the Marl. I have good opportunities of doing this at York as our series of freshwater and terrestrial shells is ample. Do they lie in layers? Any mark of peat? Any pebbles or even coarse sand in it? Bones rounded? or not. Any blue phosphate of Iron? Any land shells or indeed any shells, or any line in the Chalk rubble of the top? Sand level over all? Depth to the Red marl. It is worth while to ascertain this by boring (not now, but when the interest is made apparent and subscriptions can be raised)?[46]

Whilst Dikes could gather useful data by attempting to answer these questions, he probably would not have understood the significance of the questions. Clearly, Phillips had a good idea of those contemporary issues in diluvial geology to which this deposit might provide some explanation. It was not simply a matter of investigating and recording a curious or particularly productive deposit of bones, he saw it as having potential importance beyond the bounds of Yorkshire.

On the 30 July, Phillips sent a note to Vernon and Salmond, and dined with them that evening to discuss the discovery. They agreed to go to Bielsbeck Farm the following morning, returning to Vernon’s house at Wheldrake in the evening.[47] Phillips was, as ever, accompanied by a barometer which, from regular readings taken on the journey, would enable him to gauge the elevation of the deposit.

At Foster’s house, Phillips made hurried notes and drawings in pencil in his notebook, to be inked in later. He attempted to answer the questions that he had asked Dikes. What was the exact location and the stratigraphy of the deposit? Could erratics be used to distinguish particular layers? From which stratum or strata had the bones come? How could this type of deposit be recognised at the surface? Salmond made notes on the bones, which were much as Dikes had described them, except one which appeared to come from a lion. Phillips also made on the spot identifications of the bones:

Elephant – 2 teeth, head of humerus, 1 axis with the epiphysis on face (a bone of foot), lower jaw left side…

Rhinoceros- 2 tibiae without epiphyses, part of skull; 2 teeth upper molars of opposite side.

Ox – vast horns (2) occupital & sphenoidal bones… vertebra 2 which fit cervical; astragalus metacarpal; calcaneum horn flat core[?]

Stag – vertebra horn like fallow? like Kirkdale

Horse – Phalangal, metacarpal, scapula, radius 4

Lion – Upper jaw 2 premolars; lower 3 molars (2 teeth); both sides but condyles improper.[48]

The section in the pit, which was now partially flooded, consisted of a thick bed of black marl which could now only partially be seen, overlain by grey marl, then by chalk and flint gravel, with a layer of sand at the surface. In the heaps of black marl, which had been removed from the pit, they extracted numerous shells – objects in which the farmer had taken little interest.

At Wheldrake in the evening, the three discussed what should be done with the information they had gathered. They obviously agreed with Phillips that it should be written up as soon as possible. Roles had been given to each of the party while at Bielsbeck: Vernon was to write the general paper himself; Salmond would identify the bones and Phillips the shells. This arrangement no doubt took into account Phillips’ imminent departure.

Phillips, however, was aware that the discovery was not theirs but Dikes’. Immediately on his arrival back in York on Saturday 1st August, he wrote to Dikes to inform him of their plan. According to Phillips, Dikes had been mistaken in identifying the remains of bear – these were lion – and also concerning two shell genera – Pupa and Cyclas – which did not occur at the site. But would Dikes publish?

I am anxious now to know whether you will do as I recommended; send your account to the Journals or be hooked into ours. You will doubtless prefer the former. We shall send to Phil Mag (acknowledging your prior merits and accuracy) and therefore (impudent wretches that we are) recommend you to another shop![49]

Dikes might have felt brushed aside by the York men but he did not show it. Certainly the invitation from Phillips was less than generous – they were ready to publish in haste and were to do this in one of the most popular and rapidly published journals of the time. If Dikes had any doubts about the importance of the find, Phillips, who had just completed the definitive work on the geology of the Yorkshire coast, left him in no doubt: ‘It is the most important thing yet known about such osseous remains’. Perhaps Dikes lacked the will or confidence to publish. He certainly did not seem at all disgruntled by the York plan and sent on loan additional shells, which included the genera Phillips had failed to find, and a portion of bone which he could not identify.[50] Phillips spent much of the following week completing his part of the paper – working on the shells – before setting off for Europe with Rev. William Taylor on the Sunday.[51]

With Phillips out of the country, Vernon would need to complete the project on his own. This included having borings made to understand the stratigraphy of the site over a wider area. Publication in the Philosophical Magazine would present no problems – the matter had been talked through with Phillips and Salmond, and he already had contacts at the journal. The more delicate matter to be resolved was what was to happen to the material Foster had collected? Hull could undoubtedly claim priority but the York philosophers had taken the investigation further and were indeed to realise in a material way the importance of the site. Bielsbeck Farm was owned by William Worsley[52] who, like so many wealthy landowners, lived in the north of the county – at Hovingham in the Howardian Hills north west of York. Worsley was an early member of the York society. Dikes, too, was concerned about what might happen to Foster’s bones and he approached Worsley in the hope of persuading him to deposit them in Hull Museum, only to find that Vernon had already been in contact. Worsley said he would ‘bear in mind’ Dikes’ application.[53] For the time being the bones were to remain at Foster’s house unseen by Worsley, until Phillips’ return from his tours of Europe and the South West.

In September, Vernon, Salmond and Phillips’ paper was published and an ‘account of observations made on a deposit of bones and shells near North Cliff’ by the three plus Dikes was presented by Vernon to the October meeting of the York society. In the published account Vernon takes on the lion’s share of the description and discussion, the other two simply provide appendices. Dikes is given considerable credit for the discovery and his ‘great accuracy of observation’ regarding the nature and disposition of the fauna, and for the suggestion that this represented an antediluvial bog. Vernon suggested that these exotic animals, far from belonging to a climatically different world, lived in a climate and an environment not unlike that in present day Yorkshire. Cuvier had suggested that comparative anatomy might be used to distinguish the climate for which a particular assemblage of species might be adapted; those that showed least change from current species giving a truer indication of the environment. But Vernon, having benefited from Phillips’ council, believed the invertebrate evidence was stronger. The key to the interpretation lay in the 12 land and freshwater species of mollusc still extant in Yorkshire.[54] It was quite conceivable that the beck in a former era could have provided the environment which had preserved these animals – Dikes’ antediluvial bog. Widespread gravels showed at least two deluges had subsequently inundated the region. These gravels preserved the same species as Vernon had found here.

It should seem probable that the deluge passed away without altering in any very considerable degree the condition of the earth; that the relative level of land and sea had undergone little alteration; that the climate is nearly the same, and that the species and varieties of plants and stationary animals are absolutely identical with what they were more than four thousand years ago.

The Yorkshire men were obvious disciples of Buckland, they had applied diluvial theory and created some understanding of the ecological circumstances of the time. They had confirmed the conclusions of Buckland in proving a local exotic fauna.

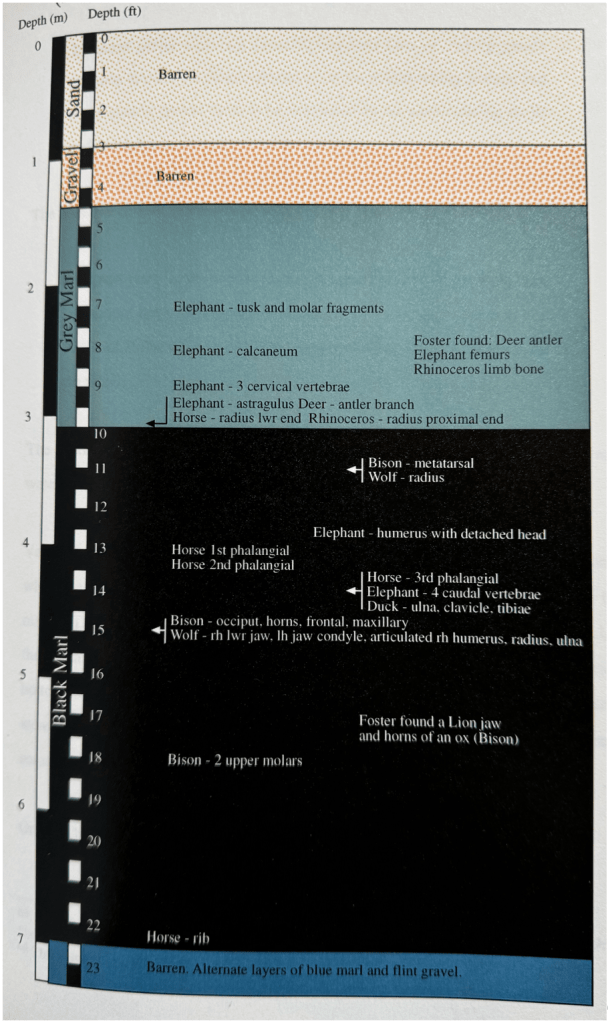

Salmond identified the bones using Cuvier’s Recherches sur les Ossements fossiles (see table 7.1) and Foster provided them with an indication of the depth from which some of his specimens had been collected:

the horns of the ox and the jaws of the Felis lay near the bottom of the excavation; the horn of the stag, the thigh bones of the elephant, and one of the leg bones of the rhinoceros lay low in the upper marl.[55]

Vernon, acting on behalf of the council of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, then set to extend the excavation, apparently employing farm labourers, probably those employed by Foster, to do the work. Vernon’s agreement with Worsley was that this excavation should principally be aimed at information gathering; the bones were to remain the property of the landowner. And no doubt Foster would also benefit from the surplus marl which would enrich the land. Vernon had a new pit sunk and superintended its excavation. Finds were measured into the section to a resolution of 6 inches. His objectives were to answer two questions. Are the organic remains stratified in any order of succession (i.e. do extinct species such as Elephas primigenius lay beneath extant forms)? And was the deposit formed under tranquil waters and subsequently penetrated by ‘the eruption of a diluvial torrent’?

Table 7.1 Bielsbeck finds at Foster’s farm July 1829.[56]

Phillips arrived back in York, from his tour of Europe and the South West, on Saturday 24 October and was soon informed of the current facts on Bielsbeck. The following Monday, he set off to Wheldrake with Vernon, travelling on to Foster’s farm the following day. Here, Phillips noted the stratigraphy – using erratics, rather than fossils, as indices for correlation with diluvial deposits elsewhere. At 14 feet deep in the ‘Black Marl’ he noted the position of an elephant humerus of considerable size – the head of which was a short distance away on its side.[57] In Foster’s house were more bones: a very flat clavicle which Phillips considered could be from an aquatic animal, and large coffin bones of a horse. The workmen had that day also found the humerus and ulna of a dog-sized carnivore. The excavation provided evidence of two different sized oxen, plates of elephant teeth, shells and plant remains. At 23 feet, the workmen were in a pebbly part of the marl, below the black marl. The fresh bones smelled ‘phosphoric’ and the marl ‘offensive’. Here the rib of a horse was found perfectly intact. Whilst several bones had polished edges there were ‘no marks of general and confused rubbing on any’. Vernon, now low on funds was coming to the end of his excavation. In all 600-700 ‘loads’ of marl were removed from the excavation during which the depths and mode of occurrence of the bones were noted. Phillips identified the bones. The exercise had cost the York society just £22.[58]

Phillips travelled back to York on the Wednesday and immediately updated Dikes with regard to Europe but more importantly developments at Bielsbeck.[59] The York excavations had added a new mollusc to the species list, as well as some bird bones and other specimens. Dikes, who still seemed contented with his lot, was preparing to lecture to his own society on the deposit and had written to Vernon requesting the use of any interesting specimens he had uncovered during the excavations and to Phillips for the shells he had loaned. He would also have liked access to the original bones, but Phillips told him these still belonged to Worsley. Phillips encouraged Dikes to visit and witness the excavation for himself but Dikes said he was unable to do so as the fishing ships were just arriving back in Hull ‘and there are so many hungry hyenas looking out for broken bones that if I am not also on the alert I shall have to dine with Duke Humphrey’.[60]

On Friday 30th October, Phillips travelled again to Bielsbeck, spending the night at Hotham, probably in the company of the Rev. E. Stillingfleet, another supporter of York’s geological exploits. On the Saturday they spent the whole day at Bielsbeck, arriving back at York late that night. The purpose of the visit seems to have been to meet Worsley, who had been very keen to see the excavation, and to bring the bones back to York.[61] Certainly this was Phillips’ last visit to the excavation.

As with his previous visits, Phillips’ first action was to give Dikes the latest intelligence. Dikes was certain to require this for his lecture as this would rely to a large extent on secondhand data. The most important aspect of the latest excavation was the palaeoenvironmental information which could be gathered from the disposition of the bones; as a whole ‘the interior of the pit presents nothing new or important’.[62] The dog-sized carnivore was now a wolf, and the occurrence of two of its forelimb bones in close association showed that the animal was not fully disarticulated at burial.

Figure 7.2 Section showing the locations of finds recorded during the excavation at Bielsbeck (including Foster’s finds)

It seems pretty clear that into this ancient lake or swamp gentle currents carried the loose substances of the neighbouring surface and these quietly spread them to be concealed by the accumulating shells and sediment.

The polished ends of the bones indicated transportation but not a flood:

No great land floods ever happened during this deposit of shells, else we should have seen layers of sediment like those above the peat and shells of Holderness – some little fragments of peat lay in the Marl but no wood.

The associated erratics also did not indicate long ‘beating and wearing in streams of water’.

Vernon too wrote to Dikes with information, and promised to send some of the bones which had been recently excavated. Vernon saw no distinction in the faunas of the two marls: ‘The bones are found in every part of both of these marls and of every kind, that is the remains of elephant for instance are near the top of the grey marl and near the bottom…’[63] Whilst no entire skeletons were uncovered the bones of certain individuals were found in close association. Amongst the finest specimens was the large, heavy and somewhat fragile skull of what Vernon called Cuvier’s aurochs or bison.[64]

On the Thursday 5 November Phillips sent the loan of shells to Hull together with:

Head[i.e. of the humerus] and Humerus of Elephant 15 ft

Metacarpal Ox 11[ft] Astrag[ulus] Elep[hant] 8[ft]

Wolf 15ft jaw, humerus, ulna, radius

Horse 14ft 3 lower leg joints

11ft long [or large?] bone worn at edges

8ft Vertebra of elephant

14ft caudal vertebra of Eleph[ant].[65]

The listing is particularly interesting for exposing the inconsistency with which the depth and identity of the specimens was recorded during their use.

Dikes was delighted with the materials and information sent from York. ‘I really am very much obliged to you for all the trouble you have had on my account and shall be glad to have an opportunity of proving it when it is in my power’.[66] There is no indication in this letter that the meeting at which Dikes had spoken on the previous day, had raised questions about Dikes’ role in the discovery. The involvement of Vernon’s team of excavators could only add to the significance of the collection when it eventually arrived in Hull. ‘The attention of the scientific portion of the public has been forcibly attracted by the exertions of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society’.[67] They had been assured by Worsley that they would receive a share of the specimens still in York.

In early December 1829, Vernon gave an account of his latest excavations to the York philosophers which he published the following January.[68] The skull of the bison was particularly important. Cuvier had remarked that it was impossible to distinguish Bovids by the bones of their extremities and that ‘no cranium had yet been discovered with the bones of the extinct elephant, rhinoceros and lion’. Now the remains of this animal could be used to suggest, using Cuvier’s methodology, that the elephants which lie above it in the same deposit must have occurred in the same cold or temperate environment as the bison. The shells were exclusively associated with the bones in the black marl; they were not present in the overlying marl.

As for Vernon’s interpretations of the conditions of deposition, the bones in the black marl showed no signs of rolling and no stones of any size occur in or below this deposit. The underlying gravels and marls are of riverine origin; the black marl formed in a mere surrounded by marshes. The grey marl formed as the embankments of the mere failed and more frequent tides overflowed the area causing shell deposition to cease.

Vernon did not use the secondhand stratigraphic data Foster had given regarding the occurrence of finds in the first pit; confirming Phillips’ principle that to interpret, one must observe for oneself. If the upper echelons of science lacked respect for the ideas of the provincial scientist, the provincial scientist also lacked faith in their non-philosophical allies. Foster’s information, however, appears reliable, placing rhinoceros and elephant remains in the upper marl; and lion[69] and ox in the lower – an interesting consistency with those measured from Vernon’s section where bovidae and carnivores are also restricted to the lower deposit.[70] Particularly so as these were separate excavations. Phillips’ later account of the fauna,[71] which largely repeats Vernon’s description, also suggested that the ‘Remains of quadrupeds… were found both in the black marl and in the superior marly gravel deposits’. He too saw no difference in the make-up of the fauna in each deposit.

At the annual meeting in February 1830, the Council of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society congratulated itself on the active part it took in the discoveries at Bielsbeck – ‘the most remarkable geological phenomenon which has been observed since the first institution of the Society’.[72] Particular thanks were given to Worsley for ‘the facilities’ and ‘for the regard which he has shown to the interests of the Museum’ implying a donation of material. Concern now began to well up in Hull over the fate of the collection, amongst rumours that Sedgwick might get a second bite of the cherry for his Cambridge museum. Information concerning the site had reached Sedgwick via William Worsley’s brother, and honorary member of the York society, the Rev. Thomas Worsley[73] of Downing College, Cambridge, who had encouraged his brother to make the donation to the Cambridge museum. Worsley wrote to console Dikes – Sedgwick would have to wait until after the other claims had been considered. Vernon also followed this line – saying that such duplicates as might be sent to Cambridge would be at the say so of Phillips and Dikes. In writing to Dikes, Vernon made his claim: he had paid the tenant £22 (of which £10 had come from the York society); Worsley as a member of the York society wished that society to be given first consideration on the understanding that the finds would not be monopolised.[74]

A few days later Phillips wrote to Dikes to clarify how the collection should be shared. Phillips could do little but confirm Dikes’ fears:

It may possibly have appeared to you that this collection of bones is rich enough to supply more than one complete series of the different animals and you may perhaps in consequence have supposed that the Yorkshire Philosophical Society has taken possession of an undue number of the specimens.[75]

Phillips listed the thirty-two best preserved items from the original excavation made by Foster – the material which Dikes had first seen and brought to the attention of Phillips. These items had, in Phillips’ opinion, to be kept together ‘wherever they were placed’, though it seems that this was inevitably to be York. Surplus material consisted of just 7 or 8 specimens: Lion (femur), mammoth (3 teeth portions (not traced); head of humerus; vertebra from tail), rhinoceros (one tooth, 2 small fragments of tibia), bison (base of skull, two horn fragments, two vertebrae, metatarsal), horse (fragment of radius). In addition the YPS could offer: bison (metatarsal; rib) and Horse (3 phalanges; portion of radius) from its own excavations.[76]

Dikes was invited to visit York to see the transaction through. But Phillips warned:

It is very much wished that no disagreement as to the partition should interrupt the harmony of two Societies so similar in their plans and objects, nor do I fear this will happen: – but however this may be, I demand for myself a perfect immunity from any discussion as my labour is anatomical not diplomatic: it relates to the classification and not to the disposal of the bones.

In other words if Dikes disagrees he should take the matter up with Vernon, who had already expressed how he saw the matter; the decision on how to subdivide the bones according to the needs of science, it appears, had been made by Phillips. Dikes was incensed by the arrangements. Phillips tried to calm the waters and again claimed immunity from any decisions made:

as I did not know of his (Mr Vernon’s) intentions on the subjects you will do me no justice to except my name from any reflections connected therewith, as that of one who was not consulted on the subject nor made acquainted with the matter till it was done…[77]

Whilst Phillips might attempt to remove himself from the controversy that was brewing, it would be all too obvious to him how unsatisfactory were the arrangements suggested in his last letter. The relationship between Dikes and the Yorkshire Philosophical Society seems to have been considerably dented. Phillips’ best friend in Hull, John Edward Lee, wrote to him in July and still Dikes felt hard done by: ‘I have just seen your note to WHD you never can appease my wrath in as much as I have none to appease’.[78] Phillips later wrote that the whole collection of bones and shells had been placed in the Yorkshire Museum; though it is certain that Hull did, in 1830, receive the fragmentary remains listed by Phillips.[79]

The Bielsbeck deposit was to remain of considerable interest to Pleistocene geologists.[80] In 1835, Phillips[81] summed up the significance of the finds as demonstrating a local fauna, with tropical animals adapted to a cooler climate, and which existed prior to the deposition of the diluvium which carried with it Cumbrian rocks. The excavation was also important for the rigour with which it was conducted; a unique example of Bucklandian cave investigation with its careful noting of strata, transferred to an open site.

Sedgwick, in his presidential address to the Geological Society in February 1830, congratulated Vernon on his zeal and fidelity: ‘Phenomena like these have a tenfold interest, when regarded as the extreme link of a great chain, binding the present order of things to that of older periods in which the existing forms of animated nature seem one after another to disappear’.[82]

The discovery at Bielsbeck had just come to public attention as Charles Lyell finished his Principles of Geologyinto which he rapidly inserted an account taken from Vernon’s papers.[83] Unfortunately, Lyell’s account was in error, increasing the depth of the pit ten fold.[84] In 1846 William Williamson undertook a comparison of the diluvium of Yorkshire and Lancashire. He could not believe the published account and needed to be convinced of its integrity. In particular he found it hard to believe that the fossiliferous deposit could have remained in situ subjected to a succession of inundations from the sea. ‘Are you convinced’, he writes, ‘beyond all reasonable doubt that the deposit at Bielbecks is inferior to and older than the great mass of pebbly clay that characterises the East coast. Is there no room for a possibility that it may be of more recent date?’.[85] Whilst the site entered local Pleistocene folklore the rigour with which the York philosophers undertook its investigation was lost from the record. Subsequent excavations sought to improve on the work undertaken in the late 1820s but none did.

[1] There is no accurate early nineteenth century equivalent to this term, all fossils were antediluvial, though obviously of different ages.

[2] Boylan (1972); Orange (1973:7); Boylan (1981) has reviewed this assemblage referring it as a whole to the Ipswichian.

[3] Buckland (1822).

[4] Davy quoted in Anon. (1822a:461).

[5] ibid.

[6] Buckland (1823). Phillips (1827:138) refers to Buckland ‘as to be with justice regarded as the great advocate and interpreter of the diluvial theory’.

[7] Frances (c.1791-1857), second wife of the Earl of Morley. Home (1817); Vernon, London to Goldie, 28 May 1823, in Melmore (1942).

[8] Buckland (1823).

[9] This collection certainly surpassed that in the Geological Society of London. Report upon the Museums and Library, 19 February 1830, Proc. Geol. Soc. Lond., 15, 174.

[10] In 1840, the material filled ‘but one of 100 cases, is still the centre of the strongest attraction’. YPS (1840) Annual Report for 1839.

[11] Knell (1994).

[12] Material also found its way to the Royal College of Surgeons, British Museum, Geological Society, Oxford University Museum, the Bristol Institution and so on.

[13] In Salmond’s view the cave’s stratigraphy was barren sandy mud, overlain by a more loamy darker mud with the smell of animal matter. He suggested it was on the surface of this deposit that the bones were found; the mud had been deposited prior to habitation by the hyenas and the bones were trodden into the upper layer. Salmond argued that from the disposition of the mud, the surface of which mirrored the shape of the roof, the cave must have been filled with muddy water. His evidence lay in a single specimen – a thin piece of stalagmite with bones attached which he recalled seeing at the time. Phillips’ record of the conversation was rather dismissive; he had examined the York collections and seen no such evidence. A few months later the specimen came to light in the possession of Rev. John Graham, the Honorary Curator of Geology, who gave it to the Museum. Salmond presented his ideas at the November meeting of the YPS. OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 16. Journal 1826-1827, Saturday 2 September 1826 and Wednesday 15 November 1826; YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826.

[14] Young believed the remains drifted into chasms during the deluge and said so in exhibition, in two lectures to the Wernerian Natural History Society, and various publications. Anon. (1827a:347); Rupke (1983b:43).

[15] Eastmead believed the limestone dated from the deluge and that the hyenas were post-diluvial (see Rupke 1983b:44).

[16] Anon. (1827b:73); Anon. (1827c:223).

[17] John Braddick (d.1829).

[18] Anon. (1827c:223).

[19] Murchison to Vernon, undated fragment [date of excursion 12 June 1827], in Melmore (1942).

[20] Anon. (1827b:73).

[21] It is probable that this was Walter Wilson.

[22] ‘Cost what it may’.

[23] Buckland to Vernon, Monday 29 December 1823, in Melmore (1942). Phillips (1829:66) remarks on a tusk of extraordinary size in the collection of Alderson of Hull, found at Atwick.

[24] Anon. (1822b:154). The deposit at Atwick was to become a notable source of fine Pleistocene fossils; a combination of elephant and Megaceros remains suggesting an Ipswichian age.

[25] YPS (1826) Annual Report for 1825.

[26] YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1, Tuesday 10 August 1824.

[27] 18 June 1789 – 26 October 1851, son of a Suffolk farmer, he received training from William Smith in surveying in the early 1800s before becoming a land surveyor in 1813 in Norwich. In 1830 he emigrated to the United States.

[28] Vernon speaking at a YPS meeting on Tuesday 14 October 1823, YPS Scientific Communications vol 1.

[29] Vernon, Eaton Hall to Goldie Tuesday 11 November 1823, in Melmore (1942); YPS (1825) Annual Report for 1824.

[30] Richardson to YPS, 19 December 1826, in Melmore (1943b); YPS Daybook of John Phillips, 30 May – 1 June 1826.

[31] This is probably Barnwell. Anon. (1824b:177).

[32] McEnery to the YPS, 4 July 1826, in Melmore (1843b); YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826. McEnery first visited the cave in 1825 with William Buckland (Kennard 1945:163 & 196-7). He became part of Buckland’s collecting network and it may have been as a result of the latter’s recommendation that material was sent to York. Pengelly (1869) published the whole of McEnery’s manuscript record of his cave researches.

[33] Anon. (1824a:64); YPS Daybook of John Phillips, 22 May 1826.

[34] Megaceros giganteus, a giant deer.

[35] Anon. (1821:150); Hibbert (1825). Charlesworth (1847:87) reports a contemporary rumour that the specimen had actually come from Dublin and that the Duke was duped. See also Davis (1889:293ff).

[36] OUM Phillips Box 81 folder 14(i) Tour of Scotland 8 July 1826

[37] see Anon. (1827f:254); WL&PS (1827) Annual Report, 5; Phillips (1829:66) stated that this was the second Irish Elk to be found in Yorkshire. Young stated it was found in a peat bog, but Atwick is an earlier deposit probably of Ipswichian age which also produced John Alderson’s exceptionally preserved elephant tusk.

[38] Probably George Lane Fox (d.15 November 1848), a Yorkshire MP.

[39] YPS (1837) Annual Report for 1836; YPS (1841) Annual Report for 1840.

[40] Various spellings: Bielbecks, Beilsbeck, Beilbecks, Bealsbeck. Also referred to as North Cliffe. Sheppard (1932), in an appendix, printed of a series of letters held by the Hull Literary and Philosophical Society concerning the Bielsbeck material. Much of Sheppard’s interpretation is inaccurate as it ignores the role of Vernon and other sources, his main purpose was to bring to light a rift between the societies in Hull and York, a rift which he later sought to extend in a jealous attempt to diminish the York society’s county role (see Pyrah 1988:25). Unfortunately, whilst Sheppard’s printed extracts appear to include almost entire transcriptions of letters, it has been impossible to trace the originals which may well have been destroyed during WWII along with the Museum.

[41] see Knell (1994).

[42] Mitton, Harrogate, to Danby, Tuesday 20 December 1825, in Melmore (1943b). Harswell lies less than three miles NE of Bielsbeck.

[43] YPS (1826) Annual Report for 1825; Danby, Swinton to YPS, 29 November 1826, in Melmore (1943b)

[44] The spelling of Bielsbeck farm is also variable. Phillips gives Foster’s residence as Biel beck House. OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 21. Diary 1829.

[45] Phillips to Dikes, Monday 27 July 1829, in (Sheppard (1932); Phillips notes the arrival of a letter from Dikes on Wednesday 29 July. OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 21, Diary 1829). Phillips (1835a:143) ‘I lost no time in proposing …an excursion to the locality’.

[46] Phillips to Dikes, Monday 27 July 1829, in (Sheppard (1932) (but see note on date above).

[47] OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 18. Notebook 1828; OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 21. Diary 1829.

[48] OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 18. Notebook 1828. It is likely that they had taken Cuvier’s Recherches sur les Ossements fossiles des Quadrupedes which the Society had purchased in 1825-6.

[49] Phillips to Dikes, Saturday 1 August 1829 in Sheppard (1932); OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 21 Diary 1829.

[50] Sheppard (1932:172) says that the only important bone from this deposit to reach Hull is a metatarsal of a lion (‘Felis spelaea‘) though he had no idea why it alone should be in the collection. It seems likely that this was the bone Dikes had found on his first (and only) visit as he would later have no difficulty in putting a claim upon this at least.

[51] OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 21, Diary 1829; Dikes to Phillips, [n.d.] sent prior to Thursday 6 July 1829 as this is when Phillips examined its contents OUM Phillips 1829/29.

[52] William Worsley (1792 – 5 March 1879), of Hovingham Hall, Whitwell-on-the-Hill, near York. Made a baronet in 1838. See Boase (1892); The Times, 7 March 1879, 9.

[53] Worsley to Dikes, Saturday 15 August 1829, in Sheppard (1832).

[54] Vernon, Salmond and Phillips (1829); The shells were donated to the YPS at this meeting – they were the only specimens the York men possessed, YPS (1830) Annual Report for 1829.

[55] Vernon (1830:226).

[56] Bones collected by Foster and identified and interpreted by Salmond (probably assisted by Phillips). Shells collected by Dikes and Phillips; identification and interpretation by Phillips.

[57] Phillips sketches the humerus, in which the body and head of the bone were separated, in his notes, OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 21 Diary 1829. These specimens were collected that day, and subsequently included in the stratified section Vernon placed in his second paper where he gave the depth of the humerus as 12.5ft.

[58] Phillips (1875:12-8); YPS (1830)YPS Annual Report for 1829, 17.

[59] OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 21, Diary 1829; Phillips to Dikes, Wednesday 28 October 1829, in Sheppard (1932).

[60] Dikes to Phillips, Friday [n.d. but undoubtedly 30 October 1829], OUM Phillips 1829/31. A reference to the return of the whaling ships and the acquisition of material for the Museum.

[61] Phillips records ‘Friday. To Mr W with Mr Vernon’, Friday 30 October 1829, OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 21, Diary 1829.

[62] Phillips to Dikes, Sunday 1 November 1829, in Sheppard (1932).

[63] Vernon to Dikes, Monday 2 November 1829; Vernon to Dikes, Tuesday 3 November 1829; both in Sheppard (1932).

[64] This was in fact a bison and not an aurochs.

[65] OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 21 Diary 1829. The elephant humerus with separate head recorded at 15ft, was recorded as from 14ft at the time of collecting, and later as 12.5ft in Vernon (1830). The astragulus listed here at 8ft is recorded as 10ft by Vernon. The horse lower limb bones listed here as from 14ft, were recorded by Vernon as being found at six inch intervals (13ft, 13.5ft, 14ft). The elephant vertebra listed as from 8ft is identified, by Phillips, as the calcaneum (tarsal) in Vernon (1830).

[66] Dikes to Phillips, Saturday 7 November 1829, OUM Phillips 1829/25.

[67] HL&PS (1832) Annual Report for 1829.

[68] YPS (1830) Annual Report for 1829; Vernon (1830).

[69] Though referred to as ‘Felis’ the remains are assumed to be lion rather than any other cat as Dikes had originally identified them as bear.

[70] This distinction appears not to have been noticed by any of the original excavators, or subsequently.

[71] Phillips (1835a:147).

[72] YPS (1830) Annual Report for 1829.

[73] Thomas Worsley (15 July 1797 – 16 February 1885).

[74] Worsley to Dikes, Saturday 13 March 1830; Vernon to Dikes, Thursday 25 March 1830; both in Sheppard (1932).

[75] The first of two letters from Phillips to Dikes, Tuesday 30 March 1830, in Sheppard (1932). Sheppard gives the same date for this letter as the next letter, but in his comments suggests that it followed a response to the first, it seems likely the dates are muddled and this is somewhat earlier.

[76] Sheppard (1932:178).

[77] Second letter, Phillips to Dikes, Tuesday 30 March 1830, in Sheppard (1932).

[78] Lee, Hull to Phillips, 2 July [probably 1830], OUM John Edward Lee 77 [n.d. 182]

[79] Phillips (1835a:144). Blake (1874:75) later listed the collection present in the Yorkshire Museum and this seems to bear out Phillips’ assertion; though Phillips appears to have meant that all the important material was in York. In 1904 Sheppard (1904:103) says other Bielsbeck specimens were on display in the Hull Museum at that time: lion metatarsal and femur, mammoth, rhinoceros, bison, horse and deer. Sheppard (1832:179) gives the entry in the list of acquisitions: ‘W Worsley, Esq, Hovingham, Whitwell. Collection of fossil bones discovered on his estate at Bielsbeck near North Cliff’.

[80] Further excavations took place in 1849 (De Boer 1958:197; Dawkins 1866). Blake (1874:75) undertook excavations in 1873 and found more material. He also re-examined the collection then in York. Whilst he believed the fossils gave only a poor indication of age, he suggested the deposit was probably postglacial. Specimens dating from this time got onto the fossil market – Hull Museum acquired some from Dr F. Krantz of Bonn in 1908 (Sheppard 1932:179). In 1904 Sheppard’s lion metatarsal, which I suggest Dikes found, had apparently been attributed to a deposit at Hornsea. On removing the specimen from its case ‘where it had probably rested undisturbed for nearly twenty years’, Sheppard washed off a label, applied by E.T. Newton of the Geological Survey who had subsequently identified it, to reveal another apparently in Phillips’ handwriting which Sheppard believed indicated Bielsbeck origin (Sheppard 1904). The confusion arose because the specimen was displayed on the same shelf as Hornsea specimens simply for convenience! The BAAS undertook further excavations in 1906 under the superintendence of Prof. P.F. Kendall and others, and whilst confirming the position of the deposit on the Keuper Marl found no evidence to accurately date it to before, during or after the ‘Glacial period’. It formed in a boggy hollow and there was no material at the locality associated with the agency of ice – the overlying gravel being derived from meltwaters. The site of Vernon’s excavation was still visible as a reedy pond. Bones, molluscs, seeds and beetles were collected (Stather 1908). Further trenching was undertaken in 1908 to determine the extent of the deposit, and yet more bones were collected (Stather 1910). The deposit was briefly reviewed by De Boer et al (1958:197-8) and Gaunt et al (1992:117); the latter suggesting that the mixed fauna given by De Boer and others suggests a need for re-examination; De Boer et al, however, point out that the mixture of species may result from inconsistencies of identification.

[81] Phillips (1835:150).

[82] Sedgwick, Presidential Address, 19 February 1830, Proc. Geol. Soc. Lond., 15, 197.

[83] Lyell (1830-3).

[84] An error copied by John Murray in a later publication. William Vernon Harcourt, Wheldrake to John Murray, Leeds, Thursday 22 December 1831, BGS IGS 1/1271.

[85] William Crawford Williamson, Manchester to Phillips, Friday 20 December 1846, OUM Phillips 1846/1.