© Simon Knell, all rights reserved. From Simon Knell, Immortal remains: fossil collections from the heroic age of geology (1820-1850), Ph.D. thesis, University of Keele, UK, 1997.

Fossil collecting from the premier localities on the north Yorkshire coast was in the control of Young and the Whitby philosophers before any of the current wave of societies had fully established their collecting intentions. This would be a source of frustration to the men of York. Scarborough, however, lay well outside the influence of the Whitby philosophers and, whilst it had no history as a depository of organic remains, through the influence of Smith and Phillips in the early 1820s it soon established a reputation of its own. For these two men this town became the centre of research, both geographically and conceptually, and they formed a useful link between it and its city neighbour.

William Vernon was keen to see this new fossil resource fuel his institution’s urgent need to acquire Yorkshire collections. For a few years this desire would not be complicated by the presence of a local society but, with increasing recognition of Scarborough’s fossil potential, interest in forming such a society burgeoned. Vernon feared that this section of the coast might also fall under local control. To prevent such an occurrence but probably in the knowledge that a Scarborough society was inevitable, Vernon undertook a week-long political campaign to win local votes; ‘communicating with the collectors there and urging them to continue their good offices in favour of the Institution’.[1] Accompanied by his geological ambassador, John Phillips, Vernon set off in his pony carriage for the coast early in September 1826. They stopped en route at Malton, another locality which had recently risen to local fossil fame. Almost equidistant from York, Scarborough and Whitby, Malton was an important territory not to be lost.

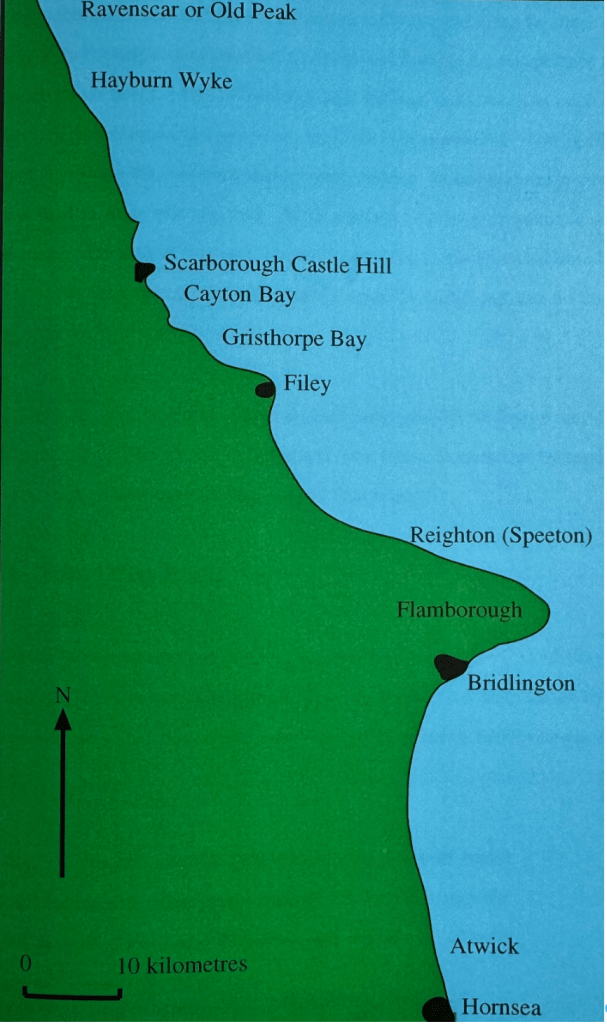

Figure 6.1 Map showing fossil localities in the vicinity of Scarborough

Taking up residence in Scarborough, the York men toured the local collectors, viewing their collections and obtaining promises of specimens. Vernon hoped to win the allegiance of three men in the town; he was already assured of that of a fourth, William Smith. Of the remaining three, John Dunn was the least experienced collector but since he drew his energies directly from the inspirational lectures of Smith and Phillips, he was perhaps the easiest man to attract on board. John Williamson and William Bean were, in contrast, proficient collectors, as well as cousins and rivals; ‘naturalists by profession’, who by 1829 would be as well known on the continent as they were locally.[2] It was these men whom Vernon most wished to draw into the fold. Bean was the first to give assurances of supplying duplicates; Williamson, however, offered a better prize. He promised to search out an example of the fossil starfish which Bean had recently found and had no doubt proudly displayed to the York men.

Vernon and Phillips returned to York with geological notes and the 68 fossils they had collected during the trip.[3] They further consolidated their recent manoeuvres by sending some duplicate material to Bean and Williamson, and then waited.[4]

A fashion for Oxford Clay fossils

Of the rocks which most interested the York men, the newly discovered Oxford Clay of Scarborough’s Castle Hill was particularly poorly known. It could not be localised by its fossils and was only so-called because of its stratigraphic position between two well determined strata:

independently of this circumstance, no particular affinity can be traced between the friable and rather sandy shale of Scarborough, and the tough blue clay of Oxford and Wiltshire; and the fossils of both situations are yet but imperfectly known.[5]

Establishing its fauna and stratigraphic relations became an important objective for the York philosophers and local collectors, who, convinced that they could make an important contribution to science and personal fame, developed a passion for its fossils. Before the end of the month the diplomacy began to pay dividends. Bean first sent 18 Oxford Clay fossils, for which specimens from the York collections were sent in exchange.[6] Thereafter Bean and Dunn continued to send further material including a number of new fossil Crustacea.[7]

Amongst John Dunn’s gifts were the first fossils he had ever collected and the first discovered in the Oxford Clay of the Yorkshire coast. Dunn had been inspired by Smith’s dismissal of this rock as a barren ‘grey earth’, when lecturing in the town in 1824; he intended to prove this not to be the case. From this recent geological education he understood the stratigraphic potential of fossils, and collected with this in mind. But he also knew the limitations of his own knowledge; he would not act as arbiter of their scientific interest. He simply became a local pair of hands and eyes, and left any judgement of value to Phillips. The fossils themselves had not been easy to collect: ‘Beware of removing their antediluvial dust; they are as brittle as a man’s good name’.[8]However, within two years of the discovery of Scarborough’s Oxford Clay, and only two months after Vernon’s tour, the possibilities for extending this collection evaporated through over-exploitation: ‘I am sorry to say it is almost in vain attempting to get a fossil now from the Oxford Clay since the surface is so broken up by Newman[?] and our indefatigable collectors’.[9]

By 1829, Phillips suggested that the list of Oxford Clay fossils from this Yorkshire deposit was probably longer than that attached to its southern relation – a monument to the collecting vigour of the four Scarborough men. The extraction of good local Oxford Clay fossils, however, remained a problem and even in 1835, after 10 years of collecting, they could still not be relied upon as stratigraphic indicators.

Emulating William Bean

Williamson’s efforts to obtain an example of Bean’s fossil starfish took a little longer. Phillips had expected him arrive with a specimen in October 1826 on his first visit to see the York society’s collections, but he came empty handed.[10] Bean’s secrecy was well known, as John Williamson’s son remarked to Phillips some forty years later, on Bean’s death:

Your Bean has gone and all his discoveries of localities have died with him, he would never communicate them to anyone and he has left no written record of them behind him. I regret this because it occasions the saying of hard things. Though not a philosopher in the higher sense he was a true worker. Pity he was not a scientific as well as a political liberal.[11]

However, such harsh words may more clearly reflect inter-collector rivalry. Many had a much higher opinion of the man – ‘a very prince of collectors’.[12] Sir George Cayley who shared Bean’s political affiliations, saw him as the discoverer of fossil localities – ‘in the same relationship as Columbus with respect to America’ and Williamson as the follower who exploited them.[13] That Williamson, Dunn and other Scarborough collectors expended considerable energy trying to discover the source of Bean’s fossils, tends to confirm this view of Bean as an extremely able fieldworker.

Bean may, however, have had good reason to remain secretive. As he explained in his paper of 1839, on the Cornbrash of Scarborough, in which he did give away his localities, he had:

witnessed with regret the extent to which fossil-making has been carried on in this neighbourhood: and (we say it “more in sorrow than in anger”) such impositions have not always been confined to ignorant and mercenary dealers.[14]

This remark was, perhaps, not least pointed at the Williamsons. As John Williamson’s son admitted towards the end of the century, he and his father had played a role in the rapid decline in number of fossils found along the coast:

In the course of little more than an hour, we filled our two baskets, as well as converted our handkerchiefs into bags… our burdens were quite as much as our strength enabled us to carry… In more recent times I have travelled over the same ground without discovering a single fossil worth carrying away. On one late occasion, when twitting one of my Scarborough friends with the absence of the geological energies displayed by the townsmen of my earlier days, he retorted very truthfully “It is all very well for you fellows to reprove us in that way, seeing that you cleared the coast so completely that you left us nothing to do”.[15]

In late December 1827, more than a year after his search had started, Williamson finally contacted Phillips about the promised starfish. He had expected this search to last no more than 6 months; it had taken more than a year.[16] The letter which accompanied Williamson’s specimen was read at the January meeting of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society. Acting on local intelligence and based on his own knowledge of the strata and also Bean’s collecting habits, he eventually located their source to a bed exposed at Staithes and Robin Hood’s Bay which Phillips thought equivalent to the Marlstone of Lincolnshire and Bath.[17] It is probable that both Bean and Williamson exploited local jet workers and artisan collectors in locating these beds.

Talk of the formation of Scarborough Literary and Philosophical Society in 1826 caused alarm in York and much high level political manoeuvring aimed at protecting the interests of the county society. Nevertheless, it seemed only proper that a town so embroiled in fossil collecting should have a museum in which to display its finds. The late Thomas Hinderwell’s collection formed its foundation, passed on by Thomas Duesbury. Bean and Williamson also agreed to donate material to the value of £50.[18] However, Williamson gave his whole collection and remained in charge of it as the Museum’s curator. In contrast, Bean remained his own man; he had increasingly less to do with the society. ‘I have no connection with our philosophers and know nothing about the meeting you mention’ he told Phillips in 1831.[19]

Why should he give important material to a collection which could not match his own, which was in the care of his rival, and would simply confer a reputation on others when it was only he who possessed such extraordinary collecting powers? Bean’s collection maintained its own status despite the rivalry of societies and their networks of collectors. Phillips’ A Guide to Geology, listed collections of assistance to the student; Bean’s was the only non-institutional collection cited in Yorkshire, and one of very few of sufficient importance nationally.[20] His museum, which was regularly made available for public inspection, also featured in the local tourist guides.[21] He also managed to establish his own network of scientific contacts and thus intercept the train of geological research as it passed through the larger public collections in Yorkshire.

The plants of Gristhorpe, Saltwick and Heyburn

William Bean’s most important geological discovery was that of the fossil plant beds in Gristhorpe Bay to the south of Scarborough, late in the summer of 1827.[22] It was probably around this time that Bean wrote to Phillips claiming the discovery of ‘new & splendid’ fossil plants from Gristhorpe and two or three other localities.[23] He promised to send examples of these in a few months; ‘the impressions of several new kinds of cycadiform plants and ferns, from the strata near Scarborough (in some of which the fructification may be discerned)’ arrived in York in October.[24] He also sent specimens to the Whitby society.

William Williamson recalled the considerable impact of this small estuarine deposit of plants, discovered at a time when the vegetation of the ‘Oolitic period’ was very poorly known.[25] The 300 or so species subsequently obtained from the coastal plant beds have provided the world standard flora for the Middle Jurassic.[26] Extremely localised, each plant bed contains its own peculiar combination of species. This known flora relies upon some 500 localities of which many only produce a few species. Even the famous localities of Saltwick and Heyburn Wyke, for example, have since their discovery produced only 30 species.

The plants of Saltwick, just south of Whitby, and Heyburn Wyke, just north of Scarborough, were already being actively exploited in 1825; they were considered amongst the county’s most important fossil treasures. Here Buckland’s, Vernon’s and Young’s networks became entwined as the York society gathered specimens for Count Kaspar von Sternberg in Prague, author of Flora der Vorwelt.[27] The York men used their Whitby contacts to meet this need, sending money to Young so that he could entice Brown Marshall to undertake a search. But Young could not send some specimens because they were unique; he would only pass on duplicates. Those that he did send were simply thrown into a box, and at the York society’s request larger and more perfect specimens were omitted as they would be difficult to pack and send to Prague. Both the York and Whitby societies were purchasing plants at this time.[28] In all York acquired 98 specimens for 26 shillings. They were not well stratified or labelled, however: ‘I did not think it needful to label them, especially as I cannot give names to all the different plants’, Young told them in February 1825.[29] A few years later, Vernon eagerly acquired a large collection of fossil plants which had belonged to the late John Bird; again these specimens appear to have been unlabelled.[30]

In 1826, the York society received a letter from Sternberg giving definitive names for the plants sent to him. It is ironic that these determinations were based on specimens which had already been through three pairs of hands, and had been seen as expendable duplicates by both the Whitby and York societies.[31] Sternberg would not even see the rarer species, which remained captive in Whitby.

The French palaeobotanist, Adolphe Brongniart, was another important stimulus to the collection of Yorkshire’s fossil plants at this time. He visited York in August 1825, on his way to Scotland, where Phillips showed him the Society’s extensive collection of plant fossils. Amongst some of the poorer examples, which may have been specimens overlooked by Young, Brongniart distinguished what he thought were seeds. This Phillips was able to confirm by further collecting of more perfect material from Heyburn Wyke.[32]

The plant beds at Saltwick and Heyburn Wyke thrust Yorkshire into even higher profile in the summer of 1826. The Brora Coal of Sutherland had attracted considerable interest from Buckland and Lyell, who considered it of equivalent age to the strata of the Whitby and Scarborough coast. In June 1826, Murchison arrived in York and with Smith sailed along the coast viewing the sections which he and Phillips had correlated with the more familiar strata of the south. He was also shown Phillips’ fossil lists, sketches and sections.[33] This was seen as a particularly important event for local geology.

The discovery of the Gristhorpe beds in 1827 extended the known flora considerably and, because they had the potential to generate new species, became particularly attractive to collectors. These plants further enhanced Bean’s reputation as the discoverer of fossils, or at least they would have done had his claim not been immediately disputed by John Williamson.[34] Williamson may have found the plants independently, though past practice would suggest not. He certainly gave Gristhorpe specimens to the Society in Whitby in this year, though appears not to have given any to the Yorkshire Museum until 1830. Even Williamson’s son was uncertain as to who should have received the credit: ‘There have always been discussions respecting the share which the two cousins, William Bean and my father, were entitled to claim in this discovery’.[35]

George Cayley, however, was in little as to doubt how the injustice occurred:

Touching upon this subject, I cannot but express my regret, that Mr Bean’s fair title to the original discovery of certain new fossil vegetables has been superseded on the Continent by Mr Williamson, who, without any unfair intentions, having given them publicity, as I find in M Brongniart’s late invaluable work[36] on fossil vegetables, they are named after him… I wish that some gentlemen, qualified by local information, would give to the public a proper line of demarcation between two most valuable men; all I wish is, that each should have his due share of public applause; a man’s fair fame ought to be as much his own as his estate.[37]

In October 1827, Phillips had arrived in Scarborough where he made drawings of ‘some remarkable plants’ for Brongniart. The York men also acquired further duplicates which they sent off to Brongniart.[38] By this time, the Yorkshire Philosophical Society had established a strong relationship with the French botanist. The degree to which Brongniart was dependent upon the collecting and collections of others became apparent to Phillips when he visited Paris in August 1829: ‘certainly if his materials were to be wholly derived from his own drawers we might conclude that he had undertaken a most difficult task with inadequate means’.[39]

First public notice of the discovery in Britain appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine in November 1827:[40]

An important geological discovery has recently been made, near Scarborough, in Gristhorpe Bay, co. York, of a large deposit of fossil plants, of the coal formation, presenting many varieties hitherto undescribed and differing essentially from those of the Newcastle field. They occur in slate clay alternating with clay, ironstone, and a thin seam of coal, about half way below the high-water mark; and are principally stems and leafy impressions of tropical ferns. Several of the specimens of the frondescent ferns are of large and uncommon beauty.

In the months following the discovery, numerous individuals donated these plants to York including Cooper Preston, of Flasby Hall, and Joseph Rowntree.[41] Williamson’s son recalled the laborious task of collecting examples from these beds which were only exposed for a few hours at low tide. Pick axes and wedges were rapidly put into play to remove the overlying sandstone, then large blocks of shale were lifted and split with hammer and knife. Occasionally particularly fine specimens were also found in nodules.[42] Given the speed with which the commercial market was developing around Scarborough it is likely that dealers were soon exploiting the new deposit and selling specimens on to the local gentry.

Amongst the private collections in the town that of Dr Peter Murray[43] had, by 1850, perhaps surpassed even Bean’s.[44] Murray was the first of the local collectors to take the discovery to publication in an article almost contemporary with that of Brongniart’s book of 1828. By this time the known flora was thought to already exceed 50 species; ‘additional species are detected almost daily’.[45]

The interesting deposite at Grispthorpe Bay may be considered as a vast herbarium, of which the leaves opening to the readiest observation, offer every facility and pleasure in the examination; and not, as is the case with the generality of coal plants, surrounded with dirt, and darkness, and perils, imbedded in the roofs and sides of mines; and they resemble so many fine drawings in Indian ink, or the shadows of delicate foliage by moonlight cast upon a smooth and white ground or wall.[46]

Murray made no reference to how the plant beds were discovered; indeed he mentions no other Scarborough collector. The Gristhorpe fossils became important evidence regarding the stratigraphic localisation and environmental analysis of these floras. On Lonsdale’s arrival at the Geological Society of London, they were immediately put on the Society’s list of wants.[47] The young William Williamson would also benefit from the finds. In 1832 he was asked, via John Dunn, to contribute figures and descriptions of the Gristhorpe flora to Lindley and Hutton’s The Fossil Flora of Great Britain.

In the years that followed, the complexity of palaeobotanical specimens and the inadequacy of contemporary monographs allowed considerable scope for the subsequent re-examination of collections. Thus in 1850 Charles Bunbury[48] examined the Scarborough collections in order to describe new species and clarify the identity of many of those described by Phillips, Lindley and Hutton, and Brongniart. In 1855, Professor Achille de Zigno of Padua, having a number of undescribed plant species of ‘Oolitic’ age from Northern Italy in his possession, wished also to include described but unfigured species of other authors in a work of his own.[49] Bunbury’s earlier article had failed to figure what he saw as an Oolitic Calamite – Calamites beanii; De Zigno sought a drawing of this, which Bunbury attempted to obtain using his friend Phillips to extract the loan of the specimen from Bean. It is strange that Bunbury should have attempted to acquire the loan in this way as he had already visited Bean’s collection but perhaps this reflects Bean’s possessiveness.

The flora of the Yorkshire coast commemorates in its species names both the collectors and the taxonomists who worked on it. Many of the names are those used by the collectors themselves prior to any description, names which were respected in publication. Gristhorpe caused such a sensation that its name may well have been recorded on the specimens it produced – this was unusual for plant fossils from this coast. In the century to come the failure to record this one immutable fact – locality – would severely inhibit the science which could be drawn from the extensive collections of plant fossils formed at this time.[50]

The Cayton Bay Crustacea

One further example provides a useful indication of the differing relationships and aspirations of the Scarborough collectors during this period, as well as the fossil specialities which developed in the town. Collectors like Bean would want to be seen as connoisseurs of their material. What they valued most were specimens which they perceived as being new in terms of horizon or species, or well-preserved or rare. A fossil having a combination of these characteristics would be particularly prized.

Fossil Crustacea were reasonably well represented in the cabinets of the Scarborough collectors in 1826. Williamson had extracted a nodule containing a ‘prawn’, identical to that ‘which Kendall[51] called a Bettle [i.e. beetle]’, from the Speeton Clay late in 1824.[52] Kendall’s specimen had come from Malton. Bean and Dunn had located examples in the grey shale at the base of Castle Hill, which Smith had determined as Oxford Clay. Dunn also located a crustacean not unlike Williamson’s Speeton ‘prawn’, and Phillips added a crab’s claw to the York collections in the following spring. Further examples were supplied to the Yorkshire Museum, following Vernon and Phillips’ promotional tour of 1826.[53]

In 1830 Dunn remained committed to extracting fossils from specific strata in order to support Phillips’ comprehensive fossil lists: ‘I went on the north sands on Saturday afternoon to try to get your Society some fossils from the Cornbrash’, he told Phillips.[54] This was a typical fieldtrip, as much a social occasion as one expected to produce material. This, however, turned out be one of those days a collector would long remember and often recount:

But!!!! Lo!!! on some fortunate hit, out popped the claw of a lobster, astacus or whatever other name you like to call it. You will conceive my ravishment. Miss Louise Belcombe and Mrs Miller were fortunately beside me (I was beside myself!) I succeeded in persuading the latter to give me a slight sketch of it upon the spot, which I enclose.[55]

Despite 6 years collecting, Dunn was rather less experienced than his contemporaries; for him this was a real coup. ‘Now what am I to do with it?’ he asked Phillips. Williamson and the Scarborough philosophers suggested that as this was the first local example from this stratum it should reside in the native institution. Dunn, however, was of another opinion, despite being Secretary of that society. ‘I have surely done my part for Scarborough’, he told Phillips. This was a means to establish his own reputation:

It is but fair that those who first find should have the benefit of their discoveries, particularly if their discoveries are as limited as mine. And I do not stand here in the position which Bean and Williamson did with each other in the coal plants [i.e. Gristhorpe plants]. My claim is undisputed.[56]

Dunn had kept the claw and the mould left in the rock. He dithered, intending to send both to York, so that Phillips could return a cast of the original. But at the last minute decided to retain the claw, perhaps for his Society.

Dunn continued to search for Crustacea, apparently motivated by nodules he had seen in Bean’s collection. He may have been directed in this by Phillips. A few months later Dunn discovered a likely source. Rudd,[57]the town’s best known commercial fossil collector, had recently sold ‘a lady’ a crustacean he had found in Cayton Bay, which he said had come out of clay, though it appears not to have been collected in situ. On hearing this Dunn asked Rudd to show him the site; this he agreed to do provided he didn’t tell Bean who had sworn him to secrecy. In June 1830, Dunn and Vernon visited Cayton Bay, locating a shale, which had not previously been distinguished, packed with Crustacea-containing nodules:

we found it was a regular parting of shale (not described) between the Kelloways rock and Cornbrash. The shale is as blue as the Oxford Clay and more laminated. Full of shells and containing many nodules all of which have either blende or astaci. The shale is from 1 to 3 feet in thickness from the floor in the bight of the N extremity of Cayton Bay, and lies about 1 yard or more above the scar in the cliff on the right coming from the mill. The Cornbrash is exposed there underneath it.[58]

Vernon and Dunn returned from the Bay laden with specimens for their respective Societies. As yet neither Bean nor Rudd had gathered specimens from the shale. Dunn was especially pleased as these came from a different horizon from those he had found previously and in July, Phillips gave a paper to the York philosophers discussing the significance of the fossil Crustacea of the Yorkshire coast.[59]

This new bed seemed strangely positioned to Phillips, and he asked John Williamson to check the details, which Williamson did during the winter. He also managed to locate identical strata at the southern end of the Bay. Again, Phillips was given exact details as to how to locate the clay band:

after leaving slip cliff, at the base of the red cliff, you step onto a hard floor of Cornbrash rock full of ostra etc and as you advance towards, the mill [Cayton Mill] it rises into the cliff, with the Kelloway rock resting on it, now between those two rocks lays a tenaceous blue clay not very thick: in this clay, we found the nodules, containing the Astaci.[60]

This clay became known as the ‘Clays’ or ‘Shales of the Cornbrash’.

The search for Crustacea continued, Phillips predicting that Dunn and Williamson would also find Crustacea in the Inferior Oolite, which they did. These, the two collectors were encouraged to bring to the inaugural meeting of the British Association in York in September 1831.[61] Phillips later planned a supplement to the second edition of his volume on the Yorkshire coast, in which he would figure these recently discovered species.[62]

The birth of Scarborough as a fossil locality can be dated to November 1824 when the lectures of Smith and Phillips provided the locals with a research project: to extend the fossil lists for strata represented locally. Phillips would be given direct access to the collections which resulted, and would need to rely little upon the connoisseurship of the collectors in order to interpret them. This was, however, complicated by the secrecy of the town’s leading exponent. In order to extract the information contained in this collection Phillips encouraged other collectors in the town to seek out Bean’s localities and collect identical specimens. The consequence of this fashion for fossils, which Smith and Phillips’s lectures in Scarborough had engendered, was the rapid discovery of new localities and strata. The town also developed its own specialities in terms of the types of fossil found. Discovery, however, was rapidly followed by over-collecting and a depletion in the available resource. If science was to take advantage of the discoveries of these collectors it would often only be able to do so by utilising the collections themselves. In later years, both science and local society would bemoan the ultimate effects of this fashion for fossils: ‘The coast from Redcar to Bridlington was ransacked for its palaeontological treasures, then much more abundant than now’.[63]

[1] YPS Daybook of John Phillips, 6 – 11 September 1826 . OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 16, Journal 1826-1827.

[2] George Cayley speaking at the opening of Scarborough Museum, Anon. (1829:475).

[3] Reported at the October meeting, YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826.

[4] YPS Daybook of John Phillips, 18 September 1826.

[5] Phillips (1829:86;1835:57).

[6] YPS Daybook of John Phillips, 25-26 September 1826.

[7] YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826.

[8] Dunn, Scarborough to Phillips, York, 15 December 1826, YPS Letterbook.

[9] Dunn, Scarborough to Phillips, York, 15 December 1826, YPS Letterbook.

[10] OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 16. Journal 1826-1827, 25-26 October 1826. This visit occupied Phillips 3 hours, he was no doubt demonstrating the Museum’s value as a repository for the provincial collector, YPS Daybook of John Phillips, 26 October 1826.

[11] William Crawford Williamson, Manchester to Phillips, 7 October 1868, OUM Phillips 1868/73.

[12] McMillan & Greenwood (1972:155) quoting Dr George Johnson of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

[13] George Cayley speaking at the opening of Scarborough Museum, Anon. (1829:476).

[14] Bean (1839:58).

[15] Williamson (1896:54).

[16] It is possible that the YPS paid £6 10s for this specimen as Phillips notes sending this amount to Williamson at this time. OUM Phillips box 82 folder 17, Notebook 1827, 11 & 14 December 1827.

[17] John Williamson, Scarborough to Phillips, York, December 1827 recorded in YPS Scientific Communications for 1 January 1828.

[18] Anon. (1828a:126)

[19] Bean, Scarborough to Phillips, Friday 1 July 1831, OUM Phillips 1831/9.1.

[20] Phillips (1834). He is also listed, as Behne, in ‘List of Geological and Mineralogical Collections in Great Britain’, Edinburgh Phil. J., 21, 115, reproduced by Torrens (1979) Newsletter of the Geological Curators Group, 2, 421.

[21] Theakston’s Guide to Scarborough (1861:131); McMillan & Greenwood (1972:155).

[22] The exact location of the plant producing beds is given in Phillips (1829:79] figured in ‘No 8 Enlarged sections’ ‘At the Island’.

[23] Bean to Phillips, undated, OUM Phillips nd/125

[24] YPS (1828) Annual Report for 1827.

[25] Williamson (1896:35).

[26] Kent (1980:60).

[27] Count [Kaspar] Maria Graf von Sternberg (6 January 1761-20 December 1838).

[28] Young to [Goldie?] 1 February 1825, Melmore (1942). YPS (1825) Annual Report for 1824; WL&PS (1825) Annual Report, 2.

[29] Young to Goldie, 22 & 28 February 1825, Melmore (1942); YPS (1826) Annual Report for 1825.

[30] Ripley to Phillips, 21 July 1829, OUM 1829/15.

[31] YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826.

[32] Brongniart to Goldie, 17 October 1825, in Melmore (1843b); YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1, 9 November 1825; YPS (1826) Annual Report for 1825.

[33] YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1, 9 November 1824, 12 July 1825, 5 December 1826; YPS Daybook of John Phillips 1-2 June 1826; Phillips (1844:112). Williamson was also involved and became a correspondent of Murchison. See Morrell (1989:325).

[34] Dunn, Scarborough to Phillips, York, 1 March 1830, OUM Phillips 1830/6.

[35] Williamson (1896:35).

[36] Histoire des Végétaux Fossils (1828).

[37] George Cayley speaking at the opening of Scarborough Museum, Anon. (1829:476).

[38] Phillips (1835:ix); YPS (1828) Annual Report for 1827.

[39] OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 19a. Journal 1829, 23 September 1829.

[40] Page 449.

[41] YPS (1828) Annual Report for 1827; WL&PS (1827) Annual Report, 5; YPS (1829) Annual Report for 1828.

[42] Williamson quoted in Baker (1882:22).

[43] Dr Peter Murray (c.1783 – 1864).

[44] Bunbury (1851:179) remarks, having listed Bean and Murray as possessing particularly rich collections, ‘To the liberality and kindness of Dr Murray I am especially indebted for the opportunity of drawing as well as describing the most remarkable of these plants, and I wish publicly to express my obligations to him’. That he subsequently used Phillips as his contact with Bean may be an indication of his having had difficulties in using this collection.

[45] Murray (1828:312).

[46] ibid.

[47] Report upon the Museums and Library, 19 February 1830, Proc. Geol. Soc. Lond., 15, 174.

[48] Charles James Fox Bunbury (4 February 1809-17 Jun. 1886).

[49] De Zigno (14 January 1813 – 15 January 1892) published the results of this work in Flora Fossils Formationis Oolithicae (1856-85). Arrangement of the loan is discussed in Bunbury to Phillips, 25 November & 8 December 1855, OUM Phillips 1855/32 & 1855/33.

[50] Fox-Strangways (1904:7).

[51] Rev. F. Kendall, author of Mineralogy and Rocks including Organic Remains of Scarborough (1816).

[52] Williamson to YPS, 8 December 1824, YPS Letter Book; read January 1825, YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1; YPS (1826) Annual Report for 1825.

[53] YPS (1826) Annual Report for 1825; YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826.

[54] Dunn, Scarborough to Phillips, York, 1 March 1830, OUM Phillips 1830/6.

[55] ibid.

[56] ibid.

[57] Also known as Ruff and Reed.

[58] Dunn to Phillips, 27 June 1830, OUM Phillips 1830/19; YPS (1831) Annual Report for 1830.

[59] YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1, 6 July 1830.

[60] Williamson, Scarborough to Phillips, 21 February 1831, OUM Phillips 1831/27.

[61] Dunn to Phillips, 25 June 1831, OUM Phillips 1831/8.

[62] Even by the beginning of the next century these Crustacea had still not been properly determined (Fox-Strangways 1904:22).

[63] Baker (1882:456).