© Simon Knell, all rights reserved. From Simon Knell, Immortal remains: fossil collections from the heroic age of geology (1820-1850), Ph.D. thesis, University of Keele, UK, 1997.

The Philosophical Societies made the acquisition of visually and conceptually spectacular fossils a priority. Amongst these, fossil reptiles were particularly prized. In the 1820s there were few articulated skeletons of these animals in Britain and their true nature attracted considerable speculation. As the decade progressed such specimens were to become considerable prizes for provincial museums, capable of thrusting them to the fore within philosophical circles and elevating the small coastal town above its metropolitan neighbours. They were to become symbols of philosophical status regardless of the scientific integrity of the holding institution.

The events leading to the discovery and interpretation of marine reptiles have been reviewed by numerous authors and need no repetition here.[1] However, it is useful to give some background to the contemporary research of William Vernon’s close friend William Daniel Conybeare, who, employing Cuvierian comparative anatomy, was to distinguish and describe the three major elements of this fauna: the Ichthyosaurus, Plesiosaurus and crocodile. These he saw as closely related genera but not, as he was at pains to make clear, in an evolutionary sense. He viewed species as conforming to a general plan which had been created and then modified to fill all niches.[2] His three papers, published between 1821 and 1824, provide a useful record of the progress of discovery.[3]

When, on 6 April 1821, Conybeare came to read his first paper before the Geological Society, the Ichthyosaurus was already well-represented by a number of fairly complete specimens, and a wealth of fragmentary material. This paper provided the first detailed anatomical description of its skeleton and enabled the identification of even the most fragmentary remains. The modern crocodile, which was at this time well known and widely represented in collections, formed the basis for comparison. True fossil crocodiles were also known, though less perfectly than the Ichthyosaurus. Conybeare used material, which included a skull, found in the Middle or Upper Jurassic rocks of Gibraltar near Oxford, as well as a Portlandian specimen from the Isle of Purbeck.[4] Whilst there was considerable interest in the geological distribution of crocodiles, they were perceived as offering little challenge for the comparative anatomist; crocodilian zoology was best observed in the modern animal. Fairly complete specimens of Ichthyosaurus, however, remained highly prized and successive finds produced noticeably different species and included specimens of extraordinary size. Ichthyosaurs had modern analogies in other animal groups, although not in modern reptiles; they were remarkable but not beyond comprehension. Their skeletons were found in increasing numbers throughout the century.

The Plesiosaurus remained for a long time a mysterious giant crocodile; in April 1821, its skull and lower jaw remained unknown. Conybeare had, however, managed to isolate the paddles and much of the post cranial skeleton from fragmentary specimens. Even after the discovery of a complete specimen, these ‘strange monsters’,[5] which lacked any modern analogy, remained enigmatic and perhaps the most prized British fossil.

Conybeare’s search for the remains of the Plesiosaurus was assisted by Henry De la Beche who had been given the task of using his local knowledge to locate appropriate material for description from the fragmentary remains held by Mary Anning and other collectors in Lyme Regis. As Conybeare’s research progressed he kept De la Beche appraised of those distinguishing features which might allow the isolation of further specimens.

With regard to the Plesios. look carefully in the collections & at Miss Anning for fragments of his head – if any bit of jaw has teeth in Alveoli it must belong to it so watch this narrowly – the snout I have just got from Weymouth which I have every reason to believe belongs to a species of this animal is very like the fossil gavials – & has its nostrils distinctly similarly placed. I hope you will bring with you as many of such specimens as are portable as you can – teeth – vertebrae & odd looking bones are instructive & take little room – try & get a few instructive & cheap specimens for me – I should be willing to embark about five pounds in the speculation & fully rely upon your discretion in applying it.[6]

It was not simply De la Beche’s familiarity with Lyme Regis which made it the focus of this research, it had established for itself an unassailable position as the country’s premium locality for fossils. The two were certain that it would provide the answers they needed.

Deprived of the suites of perfect specimens available to later generations, a high value was placed on crushed and fragmentary remains. Cranial material, fragments of articulated skeletons and even isolated bones were seen as important acquisitions for provincial museums. Philosophers, particularly medical men, would attempt to emulate the great comparative anatomists both during the investigation and interpretation of these specimens. Examples of extant species became essential comparative models and were simultaneously acquired for this purpose.[7]

As research progressed so the relative value of specimens became revealed and, indeed, changed over time. Fully articulated ichthyosaur skeletons, for example, became increasingly common as the premium paid for completeness led to an improvement in collecting method, preparation and ‘presentation’.[8] Articulated plesiosaurs remained fairly elusive and prices consequently rose.

In May 1822, Conybeare returned to the Geological Society to present further clarification of these reptiles.[9]He had hoped to have come with a complete Plesiosaurus in tow but the storms of the previous winter had failed him. He did have some new insights, however. Thomas Clarke had, by this time, found a crushed plesiosaur skull in the Lias of Street and De la Beche was now in the possession of an almost perfect lower jaw, found in the previous December, possibly in the collection of Mary Anning.[10] Buckland saw this jaw at Conybeare’s house and wrote immediately to De la Beche:

I have been more delighted, than with anything fossil I ever yet beheld, by the sight of your glorious jaw of Plesiosaurus which deserves to be cast in gold and circulated over the Universe.[11]

Buckland did indeed have the sculptor Francis Chantrey[12] make some casts which were circulated widely, including to Cuvier and the Yorkshire Philosophical Society. He also retained the specimen on display in his newly refurbished museum in Oxford, where he hoped it would stay:

I hope you retain your intention of finally depositing the Plesiosaurus jaw in our collection of Bones, decidedly the richest and most instructive of its kind in the world. In the glass cases where it now stands pro tempore it will receive no more fractures but will become a monument Ore perennius.[13]

Unfortunately, while it was in Buckland’s keeping it was broken by Johann Miller who had been brought in to curate the collection. The jaw was, however, repaired and Buckland continued to lobby for its retention in Oxford, appealing to De la Beche’s vanity. At least here it would:

be more useful and seen by a greater number of individuals likely to become active geologists such as Strangways & Webb & Lyell & c. than in any other place you can possibly discover for it, & for fame’s sake (the names of the donors being now affixed to all our important presents) the eye of the whole rising generation of educated gentlemen in the country will be upon it in the Oxford Museum whilst in any county museum or city it will meet the sight of one generation at a time & we may allow 40 for one elsewhere your present if committed to the University will be 20 times as useful here than in any other possible collection…[14]

Despite the lack of a complete specimen Conybeare had a fairly clear picture of what the Plesiosaurus looked like and how its skeletal components could be distinguished. He was already aware that long and short necked varieties existed but he had to wait until the last week of January 1824, for a complete skeleton to finally appear. This was found by Anning and sold to the Duke of Buckingham for £100. Conybeare would ultimately name it Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus. This Conybeare made known almost immediately at an evening meeting of the Bristol Literary and Philosophical Society and shortly afterwards at the Royal Society Club and the Geological Society.[15] ‘I made my beast roar almost as loud as Buckland’s Hyenas’ Conybeare later told De la Beche.[16] Other material was also coming to light: a skull had been found in the collections of the Philpot sisters, collectors also based in Lyme Regis, and Buckland received a number of large bones of what Conybeare called Plesiosaurus giganteus from Market Rasen in Lincolnshire.[17]

The only material from Yorkshire known to have come before Conybeare at this time, was supplied from John Bird, via Buckland. Whitby’s relative geographical isolation had meant that it was also isolated from the major developments then taking place in geology. In terms of local rocks, those in Whitby were considered analogous to those in Lyme Regis, although the latter had, apparently, been much more productive in fossils. This is easily understood as Lyme Regis had long been a fashionable destination for the touring gentry.[18]Tourism had generated a trade in fossils and shells which would enable chance finds, as all rare fossils are, to come to light. It encouraged the establishment of a colony of collectors who could be active outside the tourist season, building up their stores from the winter cliff falls. The trade brought with it the connoisseurship necessary to distinguish important material; collectors were inevitably well briefed by those gentlemen philosophers and others who sought to purchase the most spectacular finds. In effect the market produced its own momentum as success brought increased demand and interest from further afield. Lyme Regis was monitored by all serious English collectors.

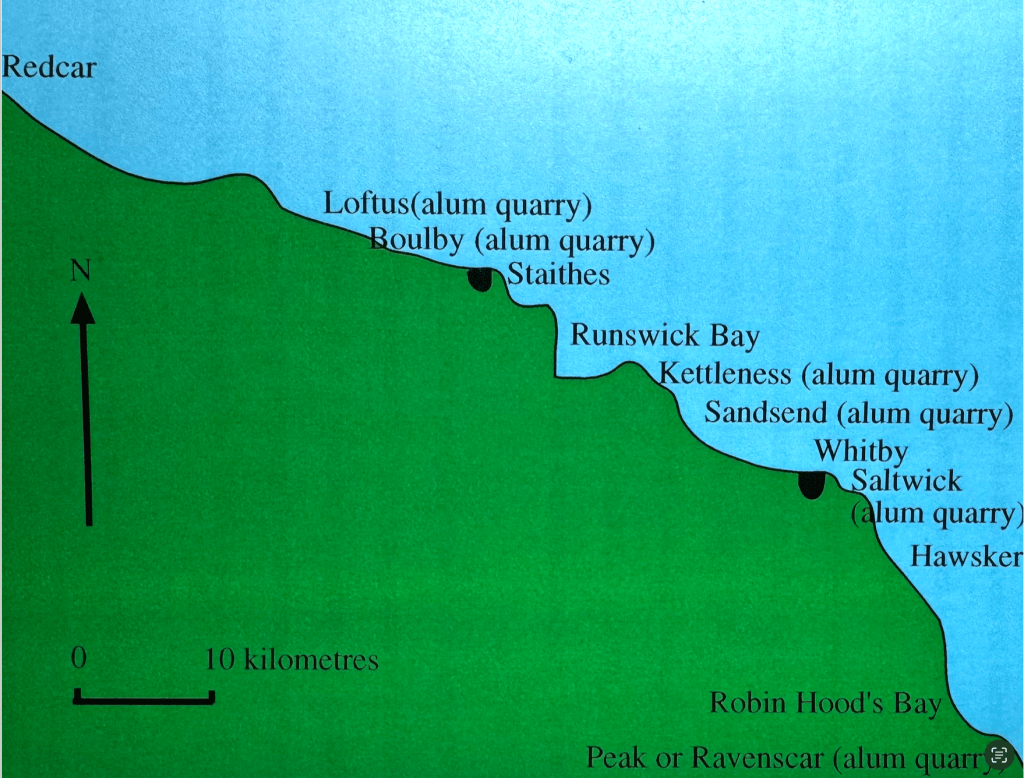

Figure 5.1 Map showing fossil localities in the vicinity of Whitby

Whitby also had its commercial collectors but in the early 1820s the market was far more restricted; sales were largely made to visiting tourists. Local dealers appear to have lacked any contacts in more lucrative markets, and were also ill-informed about the value of what they found. Certainly, Yorkshire prices were considerably lower than those on the south coast. Whilst, Yorkshire had received numerous geological tourists, they were fewer in number than those visiting Lyme and local interest in geology remained, in the period before the founding of the philosophical movement, largely in the hands of speculative philosophers such as Young and Bird and antiquarians like Hinderwell. Yorkshire geology remained in a pre-scientific age.

It was in this atmosphere of isolation that Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society sought to establish and control a market in fossils. By exclusive exploitation of such local riches they could rise above their rivals in neighbouring towns and cities. Whitby was the only town capable of doing this. York lay in a palaeontological wilderness. Scarborough, was too far from the saurian producing beds and had yet to discover its own fossil wealth. It also lacked the zealous captaincy of a Young or Vernon. Hull was even further removed.

Whitby in control

The Yorkshire Philosophical Society had been formed with the intention of taking full advantage of the fossil wealth exposed in the rocks around Whitby. But with the simultaneous formation of a local society, it found this objective difficult to fulfil. William Vernon could have patronised the local collectors had he known any. Yet he was aware that to acquire the most important, and by inference the most infrequent, finds he would need well-briefed eyes and ears in Whitby. He had no choice but to ask the town’s most noted geologists, Young and Bird, who were also key members of the Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society, to be his coastal agents.[19] Superficially this might be seen as a strengthening intersociety bonds but in reality was simply adding honour to the rivalry which existed between them; if they were to do battle for these fossils they would do so as gentlemen. Such an arrangement would, however, never give York superior collections; first class material would remain in Whitby provided the local society could pay or control the collector’s prices.

In a free market, Whitby would never be able to compete with York or the other major centres of philosophy now forming in Bristol, Cambridge, Manchester, Dublin and elsewhere. To succeed it would need to control both prices and distribution. Its own brand of protectionism would centre on active collecting, not in-situ preservation; increasingly locals would find fossils an important source of income. The local society could offer collectors both a ready market and an agency for the distribution of specimens to more distant buyers such as philosophical societies and private collectors. As exhibits of Whitby fossils became established in museums across the country they would provide an important shop window for further sales.

In this way Whitby philosophers found themselves acting as agents for both the consumers and producers; they were at the hub of fossil distribution. Everything of any significance would first pass through their hands. And being ignorant of market prices the artisan collectors were only too happy to accept George Young’s recommendations. There is no evidence that the Whitby society took a commission on sales but by assisting collectors in this way they accumulated considerable goodwill. This was reflected in first refusal on new finds and lower prices. The local society’s collection became a fluid assemblage of bones, ammonites, fossil plants and other specimens. As better specimens were purchased or acquired so older material would be sold on or exchanged. By these means the collection could be progressively improved.

Young also put collectors in direct contact with buyers. Thus during 1823, Whitby’s most prominent dealer, Brown Marshall, was able to sell 140 fossil specimens including numerous fragmentary remains of Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus to the Yorkshire Philosophical Society.[20] Local members would also see the possibilities for exchanges from their own collections. John Bird, who was a proficient collector in his own right, was soon negotiating with Vernon over the acquisition of two incomplete specimens of Ichthyosaurusfrom his collection:

one of the boxes contains the bones of an Ichthyosaurus, the detached bones of one of the paddles is very interesting as intire as any that have been found in the district. The head being crushed and mutilated was indistinct, but I have packed in the same box two parts of another head, found near the same place, and which appears to have belonged to an animal of the same size and species, which together with the other bones will make a good specimen of the Ichthyosaurus.[21]

Presented as such these remains when combined would form a useful illustration of the type, such practice would become commonplace amongst coastal dealers in the years ahead. Simple illustration might satisfy the local philosophers and was a professed objective of the larger society but the York men required more rigour. Vernon wrote back. Had Bird more data about the finding of these remains, particularly regarding their stratigraphic position? The Whitby curator seemed unwilling to give an exact locality – the most Vernon received was ‘in this district’, ‘in one place’ and with ‘aluminous rock attached’.[22] It was recorded Lias, Whitby. Bird sent only a few fragments of the ‘indistinct’ head , as an artist he probably felt it had little illustrative quality and thus the scientific integrity of the material was further reduced. Vernon would have preferred the specimen intact rather than as individual bones, and indeed this was how Bird had originally obtained it. But in the dry air of the cabinet it soon fell to pieces as the clay matrix shrank. The York philosophers could only be assured that the bones belonged to the same animal but again had no information on their association when found.

The Yorkshire Philosophical Society urgently needed material of this type but they had no control over how it was collected or the data that was extracted with it. The Whitby men seemed rather cagey about releasing exact details. The collecting arrangement also failed the York philosophers through a disharmony of objectives. They were, after all, attempting to construct a geology of the county and this more than anything relied upon good field data; the Whitby philosophers, on the other hand, were simply imposing a brand of territoriality to protect a local resource over which they felt they had dominion.

To extract the science with the specimen a philosophising gentleman would need to be on site during excavation or at least have access to the site soon afterwards. There was no one in Whitby with sufficient knowledge or field method, to undertake this work; George Young’s influence on others in the town was overpowering. Bird was a keen collector but apparently lacked an awareness of the importance of geological context or was perhaps unwilling to supply it. A further problem lay in the selection of material arriving in York; this was also being made by these lesser scientists. All the Yorkshire Philosophical Society could do was accept or refuse what was offered; they invariably accepted it.

Early in 1824 Vernon took a trip over to Whitby to examine the local society’s collections in the hope of acquiring duplicates, and purchasing specimens from collectors. These he would then personally donate to the Yorkshire society before the AGM in February.[23] One specimen Vernon particularly desired, which he saw in the Whitby society collections, was a plesiosaur paddle. But the needs of Whitby remained a priority: ‘we cannot spare it from our collection, unless we find another of the same kind’.[24] Young knew that if they could purchase a superior specimen they would be able to recoup any outlay by the sale of this duplicate. The only way Vernon could hope to gain was if Young passed up material, the significance of which he failed to see. The chances of this were not slight as both Young and Bird frequently referred to specimens as being of the ‘same kind’ suggesting that their assessment of duplication was based on superficial characters. It was probably by this means that York acquired Bird’s crocodile skull.[25]

The Yorkshire Philosophical Society placed considerable value on gifts of fossil reptile material. In its lists of donations saurians were highlighted in more general collections.[26] Thus in 1823 a donation from Vernon was recorded ‘Specimens of Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus, Whitby. 450 other fossils…’. Anthony Thorpe gave ‘Two portions of the upper jaw, and a section of the vertebrae of Ichthyosaurus, four vertebrae with ribs of Plesiosaurus, lower jaw of Crocodile’ as well as ‘Many other Fossils and Minerals’. Joseph Eglin of Hull gave an ‘Ichthyosaurus (head, vertebrae and paddles) & other fossils, Lias, Whitby’.

Whitby’s ‘inestimable’ crocodile

The advantage of the coastal society in gathering the real prizes of the fossil world was revealed in the second week of December 1824.[27] It was then that Brown Marshall found, in the Alum Shale cliffs at Saltwick, what was to become Yorkshire’s most celebrated fossil. Marshall had come across a snout protruding from the cliff face which he excavated together with a group of bones. He took the skull, potentially the most saleable part of these generally fragmentary finds, to show Young. Young was interested, presuming it to be a particularly good example of the plesiosaur; he had never seen a plesiosaur skull. As he told the York Philosophers later, he assumed that:

the heads of large marine animals found here are principally of two kinds – the one shewing large eyes, sometimes encircled with bony plates, and placed on the sides of the head; the other shewing smaller eyes, placed near together, on the upper part of the head with two deep depressions in the cranium immediately behind the eyes. The former is termed an Ichthyosaurus; the latter we have hitherto considered as the Plesiosaurus of Conybeare.[28]

Excited at the prospect of acquiring an entire plesiosaur, Young ‘directed him to be very particular, in his further researches on the spot, not only to obtain the vertebrae, but the fin-bones’. Brown Marshall returned to the site and began to excavate into the cliff at considerable risk to himself. Within a few days he had extracted a huge skeleton, 14 foot 8 inches long, which he laid out in the curved fashion in which it had been found. Young was then invited to see Brown Marshall’s prize. ‘When I went to survey the supposed Plesiosaurusjudge my surprise, when instead of an animal with fins for swimming, I found one with legs and feet, adapted for walking: instead of a fish, I found a Crocodile’.

Phillips, when he heard the news from Goldie the following January, found the ‘discovery of a genuine crocodile at Whitby… very interesting because it seems to countenance the old paper in Phil. Trans.’[29] That the accuracy of Chapman and Wooller’s[30] account was doubted is also clear from the Whitby philosophers’ summing up of the importance of this find.

The existence of the crocodile among the large animals imbedded in the alum-shale, had not hitherto been satisfactorily ascertained: but this specimen establishes the fact beyond all doubt; the animal being fully identified by the bones of its legs and feet, with some claws, and large portions of its scaly crust.[31]

Chapman and Wooller’s fossil supposedly remained in the vaults of the British Museum if it was not already lost,[32] another important non-participant in the saurian debate. This older specimen had already been the basis of argument in France where it was considered a dolphin by some, but Cuvier in 1812 was certain it was a crocodile.[33]

That crocodile remains had not been determined earlier demonstrates the fragmented nature of collections-based research at this time; important specimens remained unseen. It is obvious that the Whitby philosophers held inadequate information, as Conybeare’s articles would have assisted in distinguishing these remains but the coastal societies did not even have these in the early 1830s. Without this information, Young would have had no way of distinguishing a plesiosaur skull, having never seen one. Crocodile jaws were not uncommon finds. In addition to Chapman and Wooller’s specimen, a jaw had been recovered in 1781 and Sedgwick collected two jaws in 1821 including ‘a wonderful beauty’.[34] These disappeared off to Cambridge never to be heard of again until Owen identified them as Teleosaurus chapmanni in 1841 as part of a review of British fossil reptiles for the British Association. They weren’t seen by Conybeare who was looking elsewhere for answers to the plesiosaur riddle. In 1822, Conybeare did not doubt that the crocodile existed in the Lias but could find no evidence and would not trust old records: ‘The crocodile is said to have been discovered in the Lias, but the fact remains doubtful’.[35] Stukeley’s[36] so-called crocodile was, according to Conybeare, really a plesiosaur and Chapman and Wooller’s specimen ‘too badly drawn to afford any certainty’.[37]

Another early specimen had been owned by Bird who donated this ‘head of a fossil crocodile’ to the Yorkshire Philosophical Society in 1823.[38] This was, in the donations list, clearly distinguished from the ‘head of Ichthyosaurus’. The name Plesiosaurus was also in use in York at this time but ‘crocodile’ probably remained as a catch all term for marine saurians. The find, which pre-dates Brown Marshall’s, was lent to Buckland who was using his network of contacts to support Conybeare’s research. It seems likely that Bird donated it to York before he was fully aware of its identity as he refers to it as ‘the head of the fossil animal which I lent…’.[39] It was not seen by the York philosophers until ‘the long sought head of a crocodile from Whitby’[40] arrived back in York in September 1826 having been cleaned, prepared and identified by Conybeare. By this time the identity of the Yorkshire crocodiles had been resolved. Had Brown Marshall not found his articulated specimen, it is certain that Bird’s material, in the hands of Conybeare, would have proven the point. While Young never expected to find a fossil crocodile, Phillips’ mind was more open.

In 1824, Robert Pickering, who was establishing Malton as a rich locality for fossils from the Coralline Oolite, also donated the upper jaw of a crocodile. A lower jaw, presented at this time and possibly the same specimen, became the subject of considerable debate within the Society. It was given to Francis Chantrey ‘whose masterly chisel sometimes leaves the works of Art, to lend its aid to Science’[41] for the purposes of preparation. On its return Phillips remarked, following comparison with other specimens in the collection, that it had the dentition of Ichthyosaurus. Indeed Phillips, in 1829,[42] illustrates what to any modern observer is obviously an ichthyosaur as ‘a singular head which seems to differ from any hitherto described fossil animal’. This not only highlights the uncertainty of identifications but also the reason for it; new types of reptile were being found in various parts of Britain throughout the decade, the local observer had no reason to believe that this fauna was restricted to so few ‘types’. In the 1835 edition of Phillips’ book he replaced the words ‘fossil animal’ with ‘Ichthyosaurus’; no doubt one of his eminent subscribers, such as Conybeare, had put him right.

The price Young paid for Brown Marshall’s crocodile was just £7.[43] At the time, and for many years afterwards, it was unique in British palaeontology.[44] It is clear that the Whitby society had little money for speculation on fossils as even the low cost of this specimen thrust it into debt. Just four years earlier the Royal College of Surgeons had purchased Lt. Colonel Thomas Birch’s ichthyosaur, used in Sir Everard Home’s description of Proteosaurus, for £100.[45] In 1831 Mary Anning asked £40 for a small and perfect ichthyosaur,[46] the price perhaps reflecting the increasing number of specimens then entering the market. The first complete Plesiosaurus had also fetched £100, but this price would rise as the century progressed. Even if it was thought that less could be learned from fossil crocodiles, this was the first proven Lias specimen; the oldest and most complete fossil crocodile ever found. At £7 it was a remarkable bargain.

Brown Marshall could perhaps see the benefits of patronising the local Society – it was a captive market and an agency for other sales. Certainly Young was capable of being aggressively possessive about finds which he considered should stay in Whitby and the collector could not afford to upset such a useful ally. Alternatively it is possible that Brown Marshall was not aware of the prices specimens fetched elsewhere. He certainly had little idea of what he had found – the scutes covering its back looked to him like fin bones.[47] Young, however, knew immediately what he had: not simply a fossil reptile or the long hoped for Plesiosaurus, but something new, evocative, finely preserved and beyond the wildest imaginings of Whitby philosophers. Like other contemporary reptilian finds, this specimen was principally a treasure, an illustration, a status symbol and only to a lesser degree an artefact of science.[48] Overnight the crocodile placed the Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society in an enviable position within philosophical circles.

Young could not wait to inform his rivals in York. His Society, which could already boast Yorkshire’s most entire ichthyosaur, now also had the most complete crocodile. In describing the find to the York philosophers, he was not only asserting his Society’s superiority (at least in this one area), but also whetting their acquisitive appetite for relics of this new type of monster. The York society were easily hooked – they had to have a Yorkshire crocodile immediately. But where were these to be found? Armed with the complete specimen, Young and his colleagues went in search of other crocodile remains in the Society collections, specimens which they had mistakenly identified as Plesiosaurus. They found two such examples showing bones and, most importantly, the skull, and informed the York philosophers of their intention to sell the larger (Young does not say better) specimen. This, he said, showed more of the snout than did the new acquisition. The price for immediate delivery – £5! York replied the same day and the specimen was dispatched forthwith on 3 January 1825.

If the Yorkshire Philosophical Society was to make maximum capital out of such a purchase they would need the specimen in York when Young and Bird began to make the new find known. The deal done, and the fossil in the carrier’s waggon, Young now gave more details of what York had bought:

It is a ponderous mass, being highly pyritous. It shews the head, except the small end of the snout; and a number of vertebrae, with some other bones, will be found chiefly round the edge of the mass. Whether a chissel might discover more without injuring the specimen, I cannot say.[49]

After a deduction for packing and carriage the Whitby society made £4 4s on the sale. Young justified this as the price they had paid for the fossil in the first place and that which Thomas Hinderwell had paid ‘for a head of the same kind without any vertebrae’.[50] However, Young did not reveal the small price he had paid for the fairly complete specimen he had just acquired, a price he had largely recouped just by the sale of one fairly poor specimen.

With the purchase made and the debt partially covered, George Young could begin the process of publicity. In early January, Bird set about sketching the new skeleton. Copies were then sent by Young to the York Society, the Geological Society and to the Wernerian Society in Edinburgh, with an explanation of where all the component parts were placed relative to each other and their completeness. Following the reading of Young’s communication in York, Phillips drew comparisons with the modern gavial. He had, at the earliest opportunity, made a special pilgrimage to Whitby to see the crocodile, having been lecturing in Hull when the news reached him. On Wednesday 2nd February 1825, Young gave Phillips a guided tour of the Museum’s newly extended collection of saurians. Phillips made detailed notes on the new specimen, paying particular attention to the skull, limbs and the number and type of vertebrae. He applied no superlatives in his description; but Young would have left him in no doubt as to what he thought of it: ‘It is on the whole, the most interesting specimen of the kind ever found on this coast…’.[51] As Young told the members of Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society a week later, his publicity campaign had been extremely effective: ‘This important discovery has excited intense interest in the literary world our fossil crocodile being superior to any kind now existing in Britain or perhaps any other country’.[52]

From the two common types that had previously blinkered Young’s view of saurian finds he could distinguish ‘from specimens of amphibia and large marine animals, now in the Museum… that at least four or five kinds of these bulky inhabitants of a former world have been lodged in our alum-shale’.[53] The Whitby society was indicating a change of direction away from simple acquisition and towards local research: ‘the labours of the Society, in future years, may be the means of throwing much light on the nature and structure of these remarkable animals’. Though in reality, they saw their role as enablers of study, by collecting and making available these finds, rather than pursuing research themselves.

The acquisition of this new crocodile was to be the Society’s greatest coup. It was to raise the Museum to a new level of scientific prominence despite its lack of truly scientific motive or method. Whitby now became an essential stopping place for those with an interest in science. Every future tourist publication mentioning the town would also mention ‘our inestimable fossil’.[54] Other collectors and societies now sought specimens and by 1850 Whitby crocodile remains would be widespread. The appearance of this specimen also transformed the nature of fossil collecting along the coast. It would be increasingly difficult for the Whitby society to remain in control of future finds. The high prices paid for such material could not be kept from local collectors, as gentlemen and societies saw this as a market capable of supplying fossils found nowhere else.

York examines other possibilities

Frustration for the York men continued as poor and incomplete specimens continued to arrive from Young and Marshall. For example: ‘Brown Marshall has recently obtained a specimen of Ichthyosaurus, having one of the eyes with the hard bony plates in a distinct & interesting form’ but ‘in other respects the specimen is of little value, being much mutilated’.[55] According to Young, specimens with complete eyes were rare: ‘with the exception of one specimen in our Museum, and one in Bullock’s Museum, I have seen no other Ichthyosauruswith the eye complete’. But Young was no expert. Brown Marshall valued this specimen at 30s and flattered the York society by giving it first refusal.

By July 1825, Vernon felt that the only way to improve the situation was to visit the area himself. He asked Phillips, who was lecturing in the West Riding, if he would accompany him. Phillips was enthusiastic: ‘Nothing could give me so much pleasure as to visit with you the native country of Crocodiles & Ichthyosauri, whose remains have become so wonderfully interesting’.[56] However, Smith’s eagerness to complete their lecturing engagements meant that Phillips did not go. In the following year they would canvass the Scarborough collectors instead.

In 1826, Vernon still hoped that Society members might turn up important finds during their trips to the coast and Salmond accordingly gave the March meeting details of the localities around Whitby which had produced the Ichthyosaurus, Plesiosaurus and crocodile.[57] In the following month the Society acquired an alligator skeleton together with a depiction of the animal in life.[58] James Atkinson had also given his private collection of comparative anatomy to the Museum: ‘a collection rendered peculiarly interesting by the illustration it affords of those fossil remains of antediluvian animals, which occupy the most prominent place in the Society’s museum’.[59]

In the autumn a letter arrived from Conybeare offering to have Johann Miller prepare a series of casts of fossil reptiles in the Bristol Institution.[60] If real specimens were hard to come by casts would at least provide useful comparative material. In the late summer of 1828 they took delivery of their first consignment, purchasing a further 20 specimens in January 1830, and still more in 1837. Chantrey too, became the supplier of numerous fossil casts including that of the Duke of Buckingham’s Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus and the fine Ichthyosaurus communis in the Geological Society. Murchison also contributed a cast of the upper part of a gigantic saurian femur from Sussex in 1827.

Conybeare’s offer sparked an idea in the minds of the Society’s Council: they might not be able to compete with their coastal counterparts in fossil dealing or exchanges but they did have at their disposal a particularly rich and diverse collection. They now intended ‘to have a series of casts made from the best fossil specimens in the Museum, for the purpose of exchange with other Institutions’.[61] When the much sought after plesiosaur paddle finally arrived from the Whitby society, York responded by returning a cast of a plesiosaur lower jaw. This was quite possibly a copy of the cast of De la Beche’s ‘glorious jaw’ which Chantrey donated to York in 1824.

Yorkshire plesiosaurs in the free market

The most prized of all marine reptiles was the Plesiosaurus, an animal of extraordinary proportions and unique strangeness. Throughout the 1830s and 1840s every museum in the country desired an example. By this time the Whitby coast was becoming renowned for its fossil saurians and the fossil market was burgeoning.

Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society had acquired its best example of this animal from the sale of the late John Bird’s collection in 1829.[62] It purchased an even better, though far from perfect, specimen early in 1830. The coastal philosophers, however, remained ignorant of exactly how to distinguish plesiosaur remains and asked Phillips, a fellow of the Geological Society, if he could obtain a cut price copy of the Transactions containing Conybeare’s description.[63]

The spring of 1831 brought with it ‘a superb specimen of the Plesiosaurus’ which had been found at Hawsker just south of Whitby by Brown Lyell. It was immediately purchased by Isaac Stickney, a keen member of the Scarborough Literary and Philosophical Society for just £14. ‘It lay like the crocodile figured by Mssrs Young and Bird with its tail towards the land’.[64] The plesiosaur was placed on loan in the Scarborough Museum on condition that the Society pay interest on the purchase price until such time as it could afford to buy the specimen outright.[65] In this way Stickney could not only hope to gain the kudos of possession and supply but also a small profit.

As to the quality of this ‘superb’ specimen, John Dunn was a little more honest when he wrote to give Phillips details, enclosing a sketch by the 14 year old William Williamson. ‘Our specimen is splendid as far as it goes, but imperfect, and imbedded in very hard strata; so that the parts were exceedingly difficult to make out’.[66]Its finest feature was the unbroken series of articulated vertebrae; its weakest, the lack of both head and neck. Other parts were also ‘vague’ and ‘worn’. This was a useful illustration of the species but it was not the specimen for which Yorkshire had been waiting. Dunn sent Murchison a more positive description of the beast for the Journal of Science and to be read at the Geological Society meeting on the 16 November 1831. Size seemed to be the specimen’s most important statistic – complete, it would have measured 19ft – the same as Cuvier’s specimens from Havre and Honfleur and, he suggested, twice that of the Duke of Buckingham’s specimen.[67]

The obligation to purchase this rather poor specimen was to have a considerable impact on the Society’s ability to invest in future, perhaps better, finds. For more than two years it remained on open display, gathering dust and becoming progressively indistinct. The forty shillings required to glaze this and a few other fossils seemed like a large sum to an organisation with virtually no operational budget. When Stickney died in 1848, with the Society locked into a phase of decline, the debt had still not been paid, and with interest had increased to £18. Payment could then no longer be delayed.[68]

In March 1841, three jet workers uncovered the first complete Yorkshire plesiosaur, and probably the finest British example then known, in the cliffs at Saltwick or Hawsker. The three men, Matthew Green, and Abram and William Brookbank, much to the disappointment of potential purchasers, appeared to ‘know its value’.[69]Up to this time science, and more particularly wealthy collectors, had profited from the ignorance of the artisan collectors, especially those working the Yorkshire coast.

The 15ft long plesiosaur was placed on exhibition above Green’s shop in Haggersgate and admittance charged – 6d for gentlemen, 3d for working men and 1d for children. In the handbill that advertised the exhibition it was claimed:

Among the multiplicity of fossil petrifactions discovered in the neighbourhood of Whitby, this far surpasses all, even the famed crocodile in the Whitby Museum; indeed it is questioned whether any fossil remains were ever discovered equal to that of this wonderful species of the Plesiosaurus tribe.[70]

Enough, surely to upset the local philosophers.

As soon as the Whitby philosophers heard about the specimen they called a meeting to form a committee to enquire about the price and raise funds for its purchase. The acquisition was essential, it was after all the local society’s raison d’être – it had waited twenty years for such a fossil to come to light. However, they were shocked to find that the asking price for this important piece of Whitby’s heritage was the astronomical sum of £500. At this point negotiations were halted, but convinced that no buyer would be found the Society continued to call for subscriptions towards its purchase.[71]

The Scarborough society simultaneously made a bid for the specimen, sending John Williamson to Whitby to examine the fossil and ‘to purchase the same if approved of and attainable at a fair price’.[72] When Williamson returned without the specimen, it also maintained the belief that it could be had for a smaller sum, say £150. They asked Sir John Johnstone, who was in London, whether he would be willing to put up a loan of £100 if the remainder was raised by subscription. Johnstone recommended caution; the Society’s finances and well being were such that a speculation of this sort could put future plans in jeopardy. ‘I confess I scarcely think it would be a prudent step in us to give so large a sum for a Plesiosaurus, however perfect, possessing already as we do a good specimen of the kind’.[73] Johnstone was neither a collector nor an active philosopher, nor did he harbour great ambitions for his local museum; he was also a supporter of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society. ‘In my own opinion, so splendid an animal as this appears to be, ought to belong to a national or county collection rather than to a district museum like ours’. The York society, however, burdened by considerable debt arising from property deals, could take no part in negotiations for this fossil. Johnstone offered two possible solutions to the Scarborough society. If their present specimen could be sold for £50 then he would support the purchase. Alternatively, this plesiosaur could be purchased for exhibition in Scarborough for a season before being sold on to another buyer. In the event, the Society decided that they would not go beyond the sum of £150 but that their offer would stand.

The plesiosaur remained on exhibition in Whitby throughout the summer of 1841. The price being asked, it seemed, was too high. It was not snapped up. The summer trade in visitors to the exhibition, however, was probably considerable – a greater attraction than the philosophers’ crocodile – and made the sellers a good income. Why should they be in a hurry to sell, particularly as the longer it was on exhibition the more it would stimulate the market? At the end of the summer they could start to drop the asking price; this was to be a Dutch auction.

In September, Dr William Clark, Professor of Anatomy at the University of Cambridge, was touring the Yorkshire coast. He stopped in Scarborough where he met with Dr Peter Murray, a keen member the local philosophical society. When asked what was worth viewing in Whitby, Murray mentioned the Museum’s crocodile; he said nothing about the plesiosaur, perhaps hoping that this specimen would still find its way to the Rotunda.

Clark arrived in Whitby to discover the Plesiosaurus exhibition, greatly surprised that Murray had not mentioned it. He assumed he knew nothing of it, but this was certainly not the case. At that time the asking price remained at £500; the Whitby society’s offer stood at £150 and they had not re-entered negotiations. Apparently no-one had surpassed this offer.

Clark wrote to Sedgwick urging him to act quickly: ‘It far surpasses any thing of the kind I have ever seen. It is very nearly perfect… such a treasure cannot long be hidden… something must be done quickly’.[74] Clark, who admitted little geological expertise, urged Sedgwick to visit. But Sedgwick had heard of the Plesiosaurus from George Young who was acting as agent in the sale of a 17ft long ichthyosaur which had formerly belonged to Hunton.[75] Sedgwick was tempted. He visited Whitby for the first time in twenty years. The last time he had left with two crocodile jaws in an age before such animals were admitted from the Alum Shales, would he now carry away the Plesiosaurus?

The Manchester Geological Society had also been approached by Green and his colleagues and was considering the purchase. It wrote to Benjamin Heywood Bright for advice. As Bright told De la Beche:

A Perfect Saurian (Dolichoderius) 15 feet long has been most marvellously brought out of its rock at Whitby. It has been offered I find to the Manchester Geological Society who write to me to know whether £315 is too large a price. If perfect, & absolutely perfect as is represented, I say No.[76]

The Dublin Institution had also been offered the specimen at a price of £300.

Sedgwick arrived in Whitby shortly afterwards and the specimen was also offered to him for £300; the price did not seem excessive but as Sedgwick told Ripley at the time, he lacked the funds for such a purchase.[77]Around this time the Whitby men again re-entered negotiations, understanding that the price was now nearer 200 guineas.[78] Alterations at the Museum stopped in expectation of giving pride of place to this specimen next to ‘our great crocodile’. The Society made its offer and later said that they had obtained the agreement of William and Abram Brookbank, but had not seen Matthew Green.

However, it seems more likely that Matthew Green, who appears to have been the dominant partner, had no intention of negotiating with the Whitby society if it could be helped. From Young and Ripley’s response to the eventual sale, it is not difficult to imagine how these over-possessive men might have reacted to Green’s attempts to sell the specimen to the highest bidder. Green quickly wrote to Clark who had made an offer of £220, haggling for £250, and added ‘Now Sir to give you a clear understanding into the affair – the Whitby gentlemen are wishful to have themselves – and we don’t feel willing they should’.[79] The price on which they eventually settled was £230.

Within days of the deal being struck, and before the specimen had left Whitby, Young and Ripley wrote to William Clark, on behalf of their Society. Clark later described this missive to Sedgwick as ‘a most insolent letter’.[80] They were indignant and presumptuous:

You are aware of our negotiating for the purchase, but surely you did not know how far the negotiation had advanced, otherwise you would scarcely have felt yourself justified in stepping in between us and the prize we had good reason to consider our own. We had resolved to give 200 pounds or Guineas for it; two out of the three owners had agreed to our terms ; and while we were waiting for the concurrence of the third, viz Matthew Green, whom accidental circumstances prevented us from meeting, it appears he had correspondence with you, and on your offering him a little more, he had agreed to sell you it… It is natural for you to be zealous for the interests of your Institution, as we are for ours; but we must not forget the position which we hold in Society as gentlemen and men of honour.[81]

They begged him to give way and take a cast instead or at very least allow them to take a cast themselves. But how could Clark comply when his honour had been questioned – ‘you are in no position to ask a favour of me’, he told them.[82] His response was vitriolic. True enough Green had played the bids of Whitby and Cambridge against each other, but he had no intention of selling it to the local Society if it could be helped. Clark knew that the Whitby philosophers were still bidding for the specimen but he believed in the free market and he told them that Sedgwick ‘would have bought it without the slightest scruple (as he did other remains which he found in Whitby) had he thought it worth the money’. Clark would not recognise their small town territoriality. He was much more informed of the offers made for the plesiosaur than the Whitby men suspected, including, embarrassingly, Ripley’s role in a failed attempt to sell it to the British Museum.

To enable safe delivery of the specimen, Clark advanced Green £10 for its packing, transport and insurance. But Green had already left with the plesiosaur before the postal order arrived, probably wishing to get the specimen out of Whitby as soon as possible. It came by ship via Hull to Kings Lynn and then on to Cambridge. His partners wanted to be sure the money was properly exchanged and asked Clark to go to the bank with Green to deposit the cash so that it could be withdrawn at Whitby – ‘M Green is no accountant’.[83]They perhaps feared being duped by Green.

Young later wrote to Sedgwick in apologetic tone. The charges made against him and Clark were ‘hypothetical’ but he did not consider the specimen ‘as fairly in the open market’ until their negotiations had ceased. As ‘a Whitby fossil, we had a claim of preference to it above all other Societies’. He added:

the scientific world owes a debt of gratitude to our Society, for had it not been for the impulse given to the search for fossils in this quarter, by its formation & its efforts, many excellent specimens, now enriching museums and cabinets, would have remained undiscovered; & even this noble Plesiosaurus might have been lying quietly in its matrix. You are aware too, that we have been ready to serve other Institutions, by negociating important purchases on their behalf.[84]

Young’s statement was true enough. But he was aware that his initial successes had opened up the local fossil market and undermined his Society’s stranglehold on collecting . His wrath would now be channelled at the ‘three low-minded fellows’ who had sold the fossil and destroyed the Society’s control of the market. All that remained as a local record was Ripley’s drawing which was circulated widely and even entered local tourist guides.[85] The local philosophers mourned the loss of Yorkshire’s most impressive fossil.

Clark had bought the specimen in order to save it for the university, Sedgwick now successfully raised subscriptions for its purchase which also created additional funds for the purchase of other Yorkshire reptiles.

The Whitby philosophers succeed in the free market

Green now had a direct link to Sedgwick, and the Cambridge men access to Whitby dealers; Young had lost his grip on the market and prices began to match those paid for fossils from the south coast. The number of people collecting fossils for profit also seems to have increased. Simpson remarked, in 1842 that ‘Lias fossils are scarce along the coast, all being sold to the dealers’.[86] Green and partners, for example, now found dealing in fossils a profitable sideline. Early in 1842 there seemed to be a short-lived abundance of fossil crocodiles with at least three fairly complete specimens for sale; Young records one being dispatched to the British Museum.[87] Green sold one each to Liverpool and Cambridge for £30 a piece.[88] Previously, Young had been Sedgwick’s local agent and had in February 1841, been negotiating the sale of a partial crocodile for around £30 for Andrews, a local collector. This specimen consisted of numerous blocks containing both the skull and vertebrae making a specimen 9 or 10 feet long. These individual components had been laid out in ‘tarras’[89] ‘nearly in the order in which they seem to have lain in the rock’.[90] Ripley’s wholesale business had also encouraged the market to develop and he continued to supply collectors and museums, including selling two ichthyosaurs to König[91] at the British Museum around this time.

Young continued to actively patronise as many collectors as possible including one by the name of Crosbie,[92] who wished to sell an ichthyosaur. Young asked Sedgwick if he was interested, explaining that the ribs and paddles had been repositioned in an unnatural way ‘so as to add to the imposing aspect of the specimen’ but also to ‘have rather deteriorated its value’.[93] Collectors typically fixed the skeletons into boxes ready for display by the purchaser; loose elements being held in place with ‘tarras’. This practice would undoubtedly undermine the scientific integrity of these specimens but was so expertly carried out that it largely went undetected. As Young added in his letter to Sedgwick:

He assures me too, and he is justly regarded as a very honest man, that he did not complete it by adding [parts] of another specimen, a trick which is sometimes played; the whole bones belong to one specimen, nothing being added or taken away.

The £30 price tag was in Young’s opinion ‘far more modest than some would have asked’. Young suggested that he may be taken lower but advises ‘he is poor with a wife and young family’.

The public’s attention had been drawn to Crosbie in 1837 in an extract from a letter, by the Rev. George Howman[94] which had been sent to the Viscountess Sidmouth, published in the Magazine of Natural History. The Yorkshire coast had become increasingly attractive to tourists, and the local museums did much to promote its geological treasures:

I have been delighted with the scenery of Scarborough, Whitby, Robin Hood’s Bay & c., and not a little to find myself dwelling amidst Crocodiles, Ichthyosauri, and a hundred other rare remains of the antediluvian world, which that coast teems with. The museum of Whitby has the finest specimen of fossil Crocodile known, 151/2ft. long; from two to three additional feet being wanting to complete its jaws. I found a smaller, but perhaps more perfect, specimen, 81/2ft. long, in the possession of a poor man who discovered it, and served me as a guide; I made a very accurate drawing of it to a scale; for some of your scientific friends may like to see it.[95]

The new crocodile was in the possession of Crosbie. Howman explained that the specimen was for sale at a reasonable price, especially considering the rarity of crocodile skeletons; he had subsequently seen a more perfect 5ft long specimen in the collection of Captain Kaines of Chatham. It may have been Crosbie’s collection which had also attracted the attention of the Scarborough philosophers in the previous year, when the spate of crocodiles began to appear:

A number of fossil specimens amongst which is a fine head of a crocodile of considerable value being offered for sale, the curator is requested to endeavour to purchase the lot for £15 with a view of disposing of such as may not be wanted.[96]

The Whitby society’s fortunes recovered from the Cambridge setback in 1847 when ‘a noble specimen of that rare fossil animal the Plesiosaurus’ became available.[97] It had been excavated at Kettleness in the summer of 1844 and exhibited at the meeting of the British Association in York that year, where Edward Charlesworth gave a short notice of its discovery and compared it to ‘the celebrated specimen’ of P. macrocephalus in the collections of the Earl of Enniskillen.[98] Unlike the Cambridge plesiosaur, this had a massive head and stronger, shorter neck. The specimen was then removed to Mulgrave Castle little more than a mile from the site of its discovery. In 1847 the Whitby philosophers began a subscription to raise the £200 purchase price – with the Society’s patron and the current owner, the Marquis of Normanby, taking a £50 share. The skeleton was complete except for one hind paddle which the quarrymen had dug out and processed before the discovery was made. This was a small loss, the labourers being aware of the financial bonus such a specimen could bring.[99]

In the same year Richard and John Ripley donated a 14ft Ichthyosaurus ‘worth more than twenty guineas’, excavated from the Alum Shale at Loftus :

When these specimens are duly arranged in our Museum, it will present a superb set of Saurian animals, such as perhaps no other Museum can boast. We shall thus follow out the counsels that were given by not a few of our Literary Visitors. That as our neighbourhood presents a richer variety of fossils than perhaps any other part of the world, we should make it our grand study to render our Museum richer in such fossils that any other. The attainment of such an object is not only connected with the honour of our Society and the interest of Science, but with the prosperity of Whitby. Many strangers have been brought here by the attractions of our Museum, and when it is elevated to its high rank now in prospect, as possessing one of the finest sets of fossil organic remains of Saurian animals in the world, its attractions will be doubly powerful, and the advantages resulting to the Town and neighbourhood proportionally great.[100]

The Society celebrated its achievement in October; in the following May the man who had made it possible, George Young, died.

By the mid 1840s the market in Yorkshire reptiles was booming. Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, which had taken little prior interest in these fossils, now acquired several. The Manchester Museum also acquired a 19 foot long ichthyosaur in 1847. In the same year the York society acquired a crocodile and an ichthyosaur skull, a reflection of the Society’s renewed interest in fossils driven by Edward Charlesworth. Early in 1852 York received its most important saurian, a plesiosaur from Lord Dundas, collected from Loftus Alum Mine.[101] Whitby also benefited from other important saurian finds in the succeeding decades including, in 1854, a massive plesiosaur found near the harbour mouth by Brown Marshall, Louis Hunton’s ichthyosaur acquired in 1867, and a 25 foot long, 8 foot wide Ichthyosaurus crassimanus from Hawsker purchased for £105.[102]

Browne[103] suggests that the high prices raised by the sale of Whitby’s marine reptiles two decades after the purchase of the £7 crocodile indicate price inflation. From this we might infer a more active market or an increased desire for such specimens but this conceals the true nature of the local market in the 1820s. The price Young paid for his specimen was ridiculously low if we compare this with prices paid elsewhere or those paid by local collectors for more fragmentary material. It may have reflected a special understanding between Young and Brown Marshall. It is quite clear, however, from his dealings with York, that George Young was a shrewd businessman able to control the release of market sensitive information, and in so doing regulate both the flow of specimens to potential purchasers and, through ‘goodwill’, the prices which his Society needed to pay. As Whitby fossils began to realise true market prices the poor local society was increasingly less able to compete, but fortunately continued to find a considerable amount of goodwill.

The Alum Shale and jet industries played a part in enabling the market to develop. The latter of the two, which was undertaken by hand and without the use of explosives, was to reach a peak in the late Victorian era, employing some 1400 men and boys. It had grown on the back of early nineteenth century innovations in carving and polishing and it has been suggested that when this went into decline so did the fossil market and local dealing.[104] Alum mining in the area dates from the late sixteenth century, and by 1822, the six largest mines produced 3200 tons per annum. The last mine closed in 1871.[105] It was only with the growth of the local philosophical movement that saurian fossils would be recognised and saved before being burnt.

With widespread publicity of the Whitby crocodile it would have been difficult to keep the secret of local reptiles from richer participants in the market. The market was certain to change. Equally, as the shelves of the local societies began to groan under the weight of isolated bones their value began to drop. Articulated specimens would maintain their value, and as the relative rarity of the finds became known (plesiosaurs were far less common that other elements in the fauna) so price differentials developed.

The situation in Whitby is particularly interesting for the clarity with which it reveals the details of a collecting network and its implications for science. The York philosophers pursued a scientific objective and were well placed to attract men of high scientific calibre to view their collections. The membership included men of wealth and, by implication, men of education. Many, like Vernon and particularly Phillips, were true philosophers;[106] Young and Bird were not. Whitby, despite its aspirations, was not a cosmopolitan centre of science. Artisan collectors, like Brown Marshall, derived income and not science from the material they collected; Marshall was no philosopher. Specimens moved up a gradient of wealth, education and status. At each stage they were evaluated by an inferior scientist before being passed on. Inevitably, future use was to be restricted by this process as data, which could only be extracted in the field or on first arrival in the museum, would not be available to the final owners. Whilst scientists might eradicate some of these problems by direct field collecting, the most important and spectacular specimens remained rare and only sporadically found. The commercial collectors were probably most active, as they are today, during the winter when stormy seas accelerate coastal erosion and each new cliff fall exposes accessible and easily collected material. Many of the finds mentioned above occurred during the winter months and as the network of contacts developed so these fossils would go to market before the summer tourists arrived. Science, and the acquisition of Britain’s most spectacular museum exhibits, was to remain dependent upon the naive and the commercially motivated collector indefinitely.

[1] See, for example, Stukeley (1719); Parkinson (1811); Cumberland (1829); De la Beche (1848); Owen (1874-89); Challinor (1971:100-102); Torrens (1974); Howe, Sharpe and Torrens (1981); Taylor (in press).

[2] Conybeare does not use the term niche but refers to ‘all places and sources of sustenance’, De la Beche & Conybeare (1821:561).

[3] De la Beche & Conybeare (1821); Conybeare (1822; 1824).

[4] De la Beche & Conybeare (1821:591).

[5] Conybeare, Bristol to De la Beche, Jamaica, 4 March 1824, NMW 299.

[6] Conybeare to De la Beche, Lyme Regis [1821], NMW 297.

[7] The work of the Cuvier was well known to British provincial philosophers. Societies would acquire recent material solely for comparative purposes ‘as facilitating a discovery of the former state of the world, by comparison of the bones of animals which are now found in the fossil state, with recent analogues’ (HL&PS (1826) Annual Report, 3).

[8] Recent conservation of nineteenth century specimens has revealed the widespread falsification of completeness – what dealers would refer to as ‘improved’ specimens.

[9] 3 May 1822.

[10] Conybeare, Bristol to De la Beche, Lyme Regis, 16 December 1821, NMW 297.

[11] Buckland, Brislington to De la Beche, Lyme Regis, 20 April 1822, NMW 163.

[12] Francis Chantrey (1781-1841) was one of the country’s most celebrated sculptors, specialising in statues and busts. He was frequently called upon by Buckland and the York philosophers to undertake preparation and casting. See also Taylor (in press) for an account of Chantrey’s involvement in preparation.

[13] Buckland, Oxford to De la Beche, Bristol, 9 & 28 September 1823, NMW 169 & 170. The jaw was returned to De la Beche on the 29 September 1823. Buckland describes the damage to the specimen as a transverse fracture near the posterior extremity which was repaired invisibly.

[14] Buckland, Oxford to De la Beche, Bristol, 28 September 1823, NMW 170.

[15] Buckland (1837:vol 1, 204) later claimed that Conybeare’s remarkable skills as a comparative anatomist had enabled him to reconstruct the skeleton of the Plesiosaurus without seeing this fully articulated specimen – ‘from dislocated fragments before any entire skeletons were found’. He appears to have made this assumption because Conybeare spoke at the Geological Society while this specimen was still held up in the English Channel having been transported by sea directly from Lyme Regis. Conybeare had, however, received a fair drawing of the skeleton from Mary Anning within a few days of hearing of the discovery and it was this which formed the basis of his interpretation of the Buckingham specimen prior to its eventual arrival in London. An engraving of the specimen was given in Phil. Mag, 67 (1826), 272. Conybeare (1825).

[16] Conybeare, Bristol to De la Beche, Jamaica, 4 March 1824, NMW 299.

[17] Buckland, Oxford to De la Beche, Bristol, 28 September 1823, NMW 170, refers to these bones as belonging to ‘the Great Crocodile’. These were later described by Owen (1842:60) as Pliosaurus. Phillips notes that a Mr Wilson of Barnsley was Buckland’s supplier of Market Rasen fossils. OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 16 Journal 1826-1827, entry for 22 March 1827. The remains consisted of the tip of a lower jaw, a femur, the upper jaw. pelvic bones and scapula. For the Philpots’ collection see Edmonds (1978).

[18] Taylor & Torrens (1995); Torrens (1995).

[19] Buckland supported this approach: ‘hope you will get some fine specimens of the Ichthyosaurus & Whitby Treasures through Mr Bird and Mr Young’. Buckland to Vernon, 29 December 1823 in Melmore (1942).

[20] YPS (1825) Annual Report for 1824. Pyrah (1974) gives this as the first donation recorded by Phillips in the Society’s fossil catalogue started in January 1823, though she suggests this is backdated.

[21] Bird, Whitby to Vernon, York, 11 August 1823 in Melmore (1942).

[22] Bird, Whitby to Vernon, York, 9 December 1823 in Melmore (1942).

[23] In January 1824, for example, Young sent over a box containing a ‘specimen of singular bones of an animal of the Saurian family… promised to your worthy President’ which Vernon later donated to the Society. Young, Whitby to [Goldie?], York 22 January 1824 in Melmore (1942).

[24] Young, Whitby to [Goldie?], York 22 January 1824 in Melmore (1942).

[25] See below.

[26] YPS (1825) Annual Report for 1824, giving a reprint of donations in 1823.

[27] Young, Whitby to [Goldie?], York, 21 Dec 1824 in Melmore (1942); Anon. (1825a).

[28] Young, Whitby to [Goldie?], York, 21 Dec 1824 read to the YPS on 11 January 1825, in Melmore (1942). Young was not a fellow of the Geological Society and had no access to more accurate information.

[29] Phillips, Hull to Goldie, York, 7 January 1825, in Melmore (1943a).

[30] Chapman. & Wooller (1758).

[31] WL&PS (1825) Annual Report, 2.

[32] The collections of the Royal Society were transferred to the British Museum in 1781, but Owen could not find the specimen in 1841 (Owen 1842:74; Cleevely 1983:251). Lydekker (1888:110-1) catalogued this fossil but remarked ‘Originally the specimen was curved laterally as in the figure, but the head was subsequently chiselled out and placed in its present position’. Torrens (pers. comm.) suggests that this may have impeded the search. Browne (1946) mentions the specimen being on display in 1946.

[33] Owen (1842:74).

[34] Owen (1842:74); Quote from D.T. Ansted, Cambridge to Sedgwick, 24 December 1841, Cambridge Adds. 7652/ID/134. Sedgwick, 20 August 1869, in Seeley, Prefactory Notice, iii-x.

[35] Conybeare & Phillips (1822:266).

[36] Stukeley (1719).

[37] Conybeare & Phillips (1822:266).

[38] The donation list shows that Bird gave the head of a fossil crocodile, head of Ichthyosaurus, 57 bones of Ichthyosaurus & c., from the Lias, Whitby. YPS (1825) Annual Report for 1824, which included a copy of the donations list for 1823.

[39] Bird to Vernon, 9 December 1823, in Melmore (1942).

[40] YPS Daybook of John Phillips, 3 Oct 1826; YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1 General Meeting 3 October 1826; YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826. This specimen was subsequently repaired by Phillips, having perhaps been broken in transit, YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1 General Meeting, 12 October 1826.

[41] YPS (1825) Annual Report for 1824. OUM Phillips Box 82 Journal and Notebook 1827-8 gives R. Pickering as a contact in Malton. OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 13. Diary 1825-26, 7 March 1826 notes Phillips talk on this specimen. YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826.

[42] Phillips (1829: Plate 12 No. 2 & p165).

[43] Browne (1949:13).

[44] Owen (1842) uses this specimen extensively in defining Teleosaurus, other specimens were much more fragmentary.

[45] See Howe, Sharpe and Torrens (1981:16); Cleevely (1983:57).

[46] Buckland, Oxford to De la Beche, London, 1 May 1831, NMW 179. Buckland also informed Sedgwick, though Botfield and Saull appear to have had prior claims on the specimen.

[47] To the uninitiated they do resemble ichthyosaur paddle bones.

[48] Young & Bird (1828:287); Buckland (1842: vol 2, pl xxv); Owen (1842:74ff).

[49] Young, Whitby to [Goldie?], York, 4 January 1825 in Melmore (1942).

[50] Young, Whitby to [Goldie?], York, 4 January 1825 in Melmore (1942).

[51] Young to [Goldie?],10 January 1825 in Melmore (1942); Phillips’ notes from the meeting of 8 February 1825 YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1; Phillips impressions of the specimen can be found in OUM Phillips Box 81 folder 12: Yorkshire Coast notes 1824, 1825, 1826, 1 & 2 February 1825 where he also notes the number of vertebrae in the Society’s other prized specimen – a fine ichthyosaur [136 vertebrae]. Another specimen with 144 vertebrae had recently been sent to Edinburgh.

[52] Anon. (1825b); WL&PS (1825) Annual Report, 2.

[53] WL&PS (1825) Annual Report, 2.

[54] Browne (1949:13).

[55] Young to [Goldie?] 3 July 1827 in Melmore (1942). YPS (1828) Annual Report for 1827. See also Young, Whitby to Goldie, York, 22 Feb 1825 in Melmore (1942).

[56] Phillips to Vernon, 10 June 1825 in Melmore (1943a); Phillips, Leeds to Vernon, York, 2 July 1825 in Melmore (1943a).

[57] OUM Phillips Box 82 folder 13. Diary 1825-26, 7 March 1826.

[58] ‘Alligator’s skeleton brought to the museum’s conversation meeting’ YPS Daybook of John Phillips, 11 April 1826; Depiction of alligator by Mr Hepworth [John Doughty Hepworth of York?] mentioned by Phillips in YPS Daybook, 6 April 1826; Goldie presents an alligator, Crocodilus lucius, skeleton and mounted specimen from ‘Guiana’, July 1826, YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826.

[59] YPS (1825) Annual Report for 1824.

[60] YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1, General Meeting, 3 October 1826; YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826. YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1, General Meeting, 12 October 1826. YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1, General Meeting, 1 July 1828 at which Millers’ letter informing the YPS of the completion of the casts was read.

[61] YPS (1827) Annual Report for 1826.

[62] YPS was not informed of this specimen prior to the sale; plants were, however, purchased for them. WL&PS (1829) Annual Report, 7.

[63] George Young, Whitby to Phillips, 4 March 1830, OUM Phillips 1830/8; John Dunn to Phillips, 25 June 1831, OUM Phillips 1831/8. Rudwick (1988:259) shows there were no members of the Geological Society in any of the Yorkshire coastal towns in 1835.

[64] YPS Scientific Communications Volume 1, 5 July 1831.

[65] SL&PS Minutes of Council, 8 April 1831.

[66] Dunn to Phillips, 25 June 1831, OUM Phillips 1831/8.

[67] Dunn (1831).

[68] SL&PS Minutes of Council, 13 December 1833 & 14 April 1848.

[69] Clark, Whitby to Sedgwick, Cambridge, 25 September 1841, Cambridge Adds. 7652/ID/107.

[70] Handbill dated 7 August 1841 advertising the exhibition obviously written by someone more educated than the three sellers. Since Ripley was implicated in the attempted sale to the British Museum, this might be his work. From a poor Xerox in the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge (original in University Archives (unconfirmed), C.L. Forbes, Cambridge to M.A. Taylor, Oxford [National Museums of Scotland], 12 June 1982).

[71] WL&PS Minutes of Council, 2 April & 11 May 1841.

[72] SL&PS Minutes of Council, Monday 12 April 1841.

[73] Johnstone, London to SL&PS, Tuesday 27 April 1841, read at the council meeting, SL&PS Minutes of Council, 10 May 1841.

[74] Clark, Whitby to Sedgwick, 25 September 1841, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/107.

[75] This was certainly Louis Hunton the pioneering Yorkshire geologist who had died in 1838, see Torrens & Getty (1984). Young, Whitby to Sedgwick, 2 September 1841, Cambridge Adds. 7652/ID/106. In 1867, Whitby Museum acquired ‘a handsome present of a large specimen of Ichthyosaurus acutirostrum, which was formerly in the possession of the late Mr Louis Hunton of Boulby’ which may have been the same specimen. Simpson, Whitby to Phillips, 12 February 1867, OUM Belem/21.

[76] Bright, Bath to De la Beche, 4 November 1841, NMW 109.

[77] Young makes this clear in a later letter attempting to clear up his claims of dishonourable conduct, Young, Whitby to Sedgwick, 24 November 1841, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/111a.

[78] WL&PS (1841) Annual Report, 19.

[79] Green, Whitby to Clark, Cambridge, 27 October 1841, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/111b; Green & Partners, Whitby to Clark, Cambridge, 3 November 1841, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/111c.

[80] Young to Sedgwick, 22 November 1841, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/111a enc.

[81] Young and Ripley, Whitby to Clark, 6 November 1841, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/111.

[82] Clark, Cambridge to Young and Ripley [draft copy], 8 November 1841, Cambridge Adds. 7652/ID/111enc.

[83] John Cuthard (a Whitby grocer acting for Green & Partners) to Clark, Cambridge, 13 November 1841, Add 7652/ID/111d.

[84] Young to Sedgwick, 24 November 1841, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/111a

[85] For example, Dowson (1854:78-88).

[86] Simpson, Whitby to T.W. Embleton, 16 August 1842, in Davis (1889:163).

[87] Young, Whitby to Sedgwick, 11 March 1842, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/121.

[88] Green, Whitby to Sedgwick, 11 February, 23 & 28 March 1841, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/121a-c.

[89] Probably a rough mortar mix made with lime and fragments of the matrix rock; this type of material has been found during late twentieth century restoration.

[90] Young, Whitby to Sedgwick, 10 February 1841, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/79.

[91] Charles or Carl König (1774-1851).

[92] Also spelt Crosby.

[93] Young, Whitby to Sedgwick, 11 March 1842, Cambridge Adds 7652/ID/121.

[94] Rev. George Ernest Howman, later Little, (c.1797-1878), see Torrens (1995:266).

[95] Magazine of Natural History, 1 (NS), 1837:532.

[96] SL&PS Minutes of Council, 18 August 1836.

[97] WL&PS (1847) Annual Report, 25.

[98] Charlesworth (1844).

[99] The same cannot have been true for those working on the expanding railway network as a Plesiosaurus was uncovered and destroyed during the construction of the Ely line. Only the paddle survived (Anon. 1849).

[100] WL&PS (1847) Annual Report, 25.

[101] Phillips (1854:54); Taylor (1992:49).

[102] Browne (1949:32).

[103] Browne (1949:13).

[104] Hemingway (1958:17).

[105] Browne (1946:258).

[106] That is they pursued science objectively and ‘inductively’ according to methods approved by their contemporaries in the vanguard of geology.